As fiber networks continue to expand across data centers, enterprise campuses, and telecom infrastructures, efficient use of optical resources has become more important than ever. Many network engineers and IT professionals searching for “what is single fiber SFP” are looking for a way to reduce fiber consumption without sacrificing performance or reliability. A single fiber SFP, also known as a BiDi SFP, is designed precisely for this purpose—enabling bidirectional data transmission over a single strand of optical fiber.

Unlike traditional SFP transceivers that require two fibers—one for transmitting and one for receiving—a single fiber SFP uses wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) technology to send and receive signals simultaneously on different wavelengths. This approach not only conserves valuable fiber infrastructure but also lowers deployment costs and simplifies network expansion. In this article, we’ll start with the basics of what a single fiber SFP is, then explore how it works, how it compares to dual-fiber SFP modules, and how to choose the right one for your network.

➡️ What Is a Single Fiber SFP?

Single fiber SFP is an optical transceiver that transmits and receives data over a single strand of single-mode fiber by using two different wavelengths, enabling full-duplex communication while reducing fiber usage. Because of this bidirectional design, a single fiber SFP is also commonly referred to as a BiDi SFP module.

In traditional fiber optic networking, standard SFP transceivers require a fiber pair—one fiber for transmitting (TX) data and another for receiving (RX) data. In contrast, a single fiber SFP combines both transmission directions onto one fiber using wavelength division multiplexing (WDM). For example, one module may transmit data at 1310nm and receive data at 1550nm, while the corresponding module on the other end uses the opposite wavelength configuration.

Single fiber SFP modules are widely used in environments where fiber resources are limited or expensive, such as metropolitan area networks (MANs), telecom access networks, and enterprise campus links. By cutting fiber usage in half, they offer a practical and cost-effective alternative to dual-fiber SFP solutions—without compromising link speed, distance, or network reliability.

➡️ How Does a Single Fiber SFP Work?

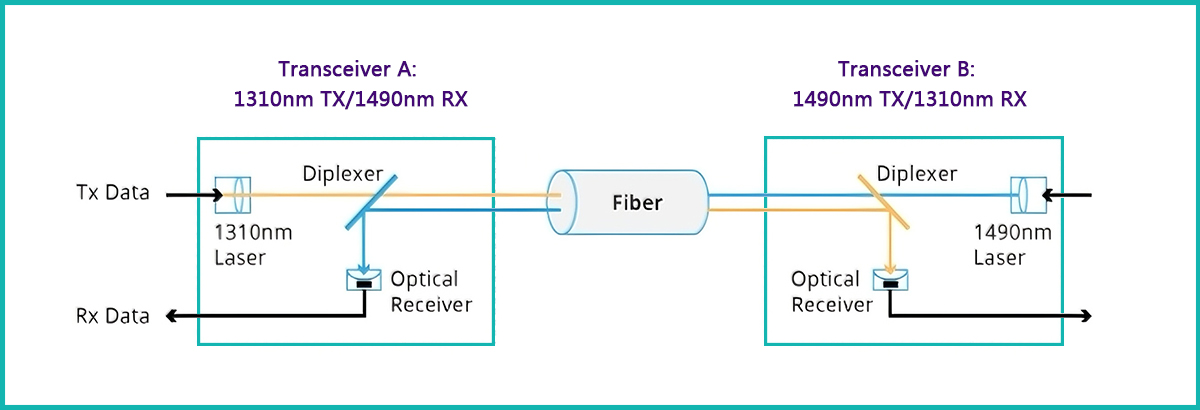

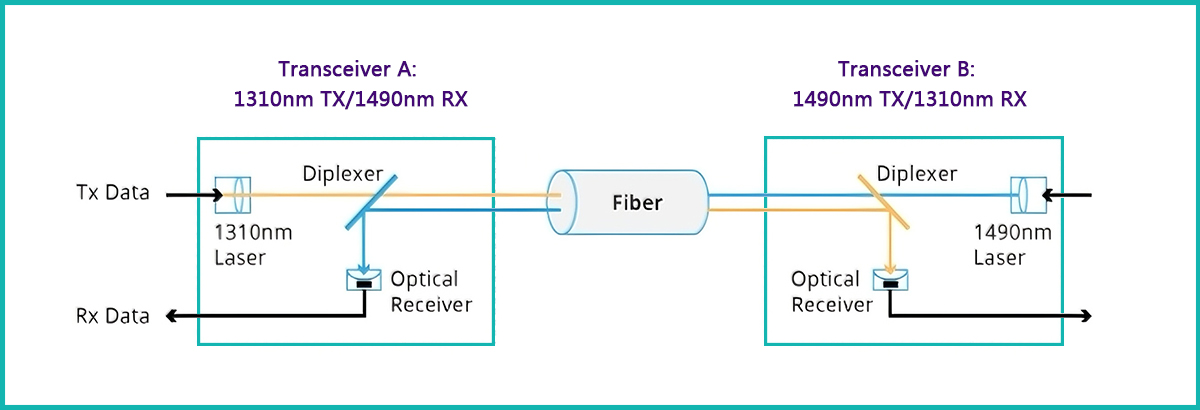

A single fiber SFP works by enabling simultaneous bidirectional communication over a single strand of optical fiber. This is achieved through Wavelength Division Multiplexing (WDM), a technology that allows multiple optical signals to coexist on the same fiber by assigning each direction a different wavelength. Instead of separating transmit and receive paths physically, a single fiber SFP separates them spectrally.

Inside the single fiber SFP module, a WDM optical component—often a thin-film filter or prism—is used to combine and split wavelengths. When the module transmits data, the electrical signal from the switch or router is converted into an optical signal at a specific wavelength (for example, 1310nm). At the same time, incoming optical signals at a different wavelength (such as 1550nm) are filtered and directed to the receiver. This allows the SFP to transmit and receive data concurrently without interference, even though both signals travel on the same fiber.

Single fiber SFPs are always deployed in matched pairs, sometimes referred to as “A-end” and “B-end” modules. These paired modules use complementary wavelengths. For instance, if the local SFP transmits at 1310nm and receives at 1550nm, the remote SFP must transmit at 1550nm and receive at 1310nm. This wavelength pairing is critical—using two identical modules on both ends will prevent the link from coming up.

From a network performance perspective, the use of WDM does not introduce additional latency or reduce throughput. A 1G single fiber SFP still delivers full 1Gbps bandwidth, just like a traditional dual-fiber SFP. The same applies to 10G single fiber SFP+ modules and higher-speed variants. The key difference lies not in performance, but in optical efficiency and infrastructure utilization.

Because single fiber SFPs rely on precise wavelength separation and optical power balance, proper link planning is essential. Factors such as fiber quality, connector cleanliness, and optical power budget become more important—especially over longer distances like 40km or 80km. When correctly deployed, however, single fiber SFPs provide a stable, standards-compliant solution that integrates seamlessly with existing Ethernet and fiber optic networks.

➡️ Single Fiber SFP vs Dual Fiber SFP: What’s the Difference?

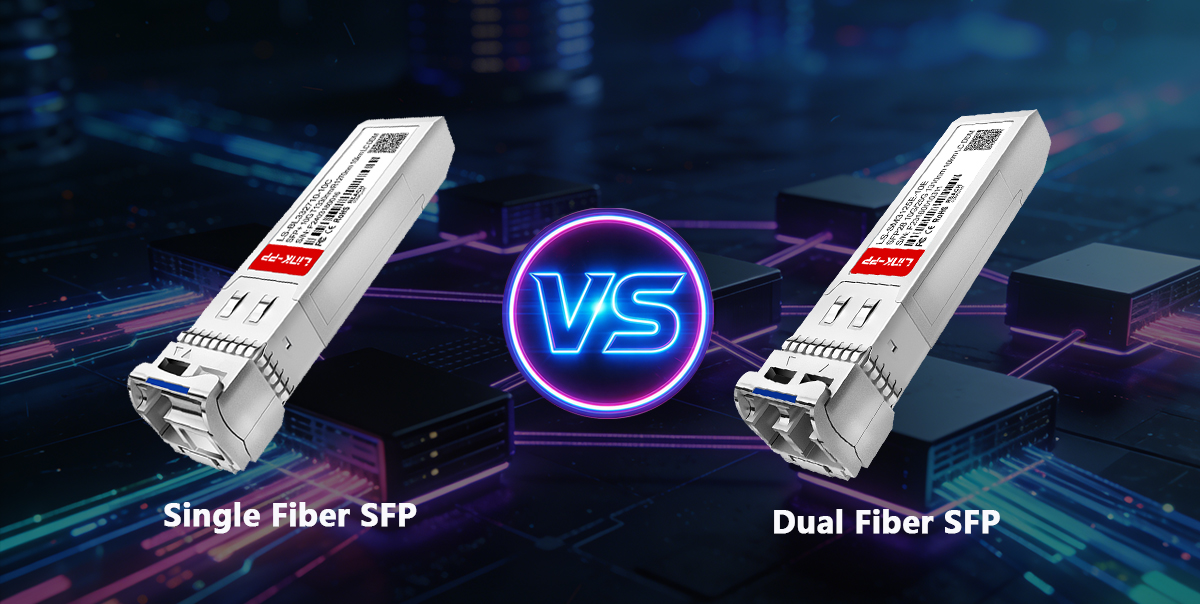

Understanding the difference between a single fiber SFP and a dual fiber SFP is essential when designing or upgrading a fiber optic network. While both types of SFP transceivers perform the same fundamental function—converting electrical signals into optical signals—their transmission methods and infrastructure requirements are quite different.

The most obvious distinction lies in how they use optical fiber. A traditional dual fiber SFP relies on two separate fibers: one dedicated to transmitting data and the other to receiving it. In contrast, a single fiber SFP uses only one fiber by transmitting and receiving data on different wavelengths. This architectural difference has a direct impact on fiber utilization, cost, and deployment flexibility.

Key Differences at a Glance

| Feature |

Single Fiber SFP (BiDi SFP) |

Dual Fiber SFP |

| Fiber requirement |

1 single-mode fiber |

2 single-mode fibers |

| Transmission method |

Bidirectional over different wavelengths |

Separate TX and RX fibers |

| Typical wavelengths |

1310nm / 1550nm, 1490nm / 1550nm |

Same wavelength on both ends |

| Module pairing |

Must be used in matched A/B pairs |

Identical modules on both ends |

| Fiber utilization |

High (50% fiber savings) |

Lower |

| Deployment cost |

Lower in fiber-limited environments |

Higher when fiber is scarce |

| Configuration complexity |

Requires wavelength planning |

Simpler |

| Common use cases |

MAN, FTTB, telecom access |

Data centers, short links |

From a performance standpoint, there is no inherent speed or latency disadvantage when choosing a single fiber SFP over a dual fiber SFP. A 1G or 10G single fiber SFP delivers the same bandwidth and link stability as its dual fiber counterpart. The difference is purely in how the optical signals are transmitted and how efficiently fiber resources are used.

However, single fiber SFPs do require more careful planning. Because they must be installed in complementary pairs with opposite wavelengths, mismatched modules are a common cause of link failures. Dual fiber SFPs, on the other hand, are more forgiving and easier to deploy in environments where fiber availability is not a concern.

In summary, single fiber SFPs are ideal for scenarios where fiber infrastructure is limited or expensive, while dual fiber SFPs remain a straightforward choice for short-distance or fiber-rich environments. Choosing between the two depends less on performance and more on network topology, fiber availability, and long-term scalability goals.

➡️ Types of Single Fiber SFP Modules

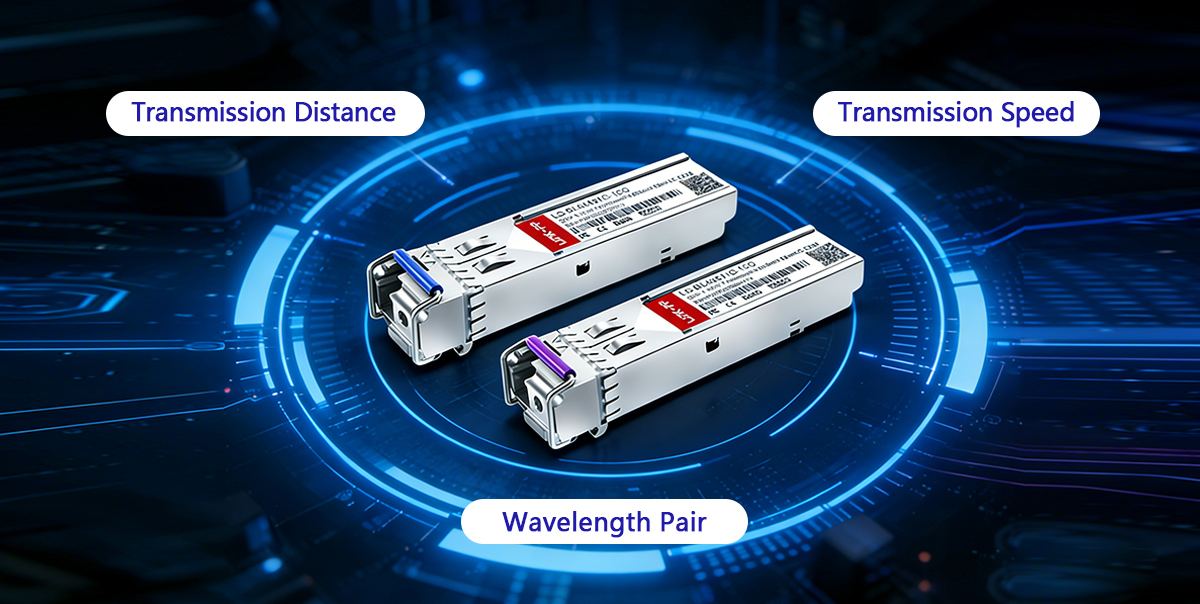

Single fiber SFP modules are available in a wide range of configurations to support different network speeds, transmission distances, and wavelength plans. Although they all share the same bidirectional transmission concept, choosing the right type depends on specific deployment requirements. Below, we break down the main types of single fiber SFP modules based on speed, distance, and wavelength pairing.

Types by Transmission Speed

Single fiber SFPs are commonly categorized by data rate. Each speed class is designed for specific network layers and use cases.

| Speed |

Common Module Type |

Typical Use Cases |

| 1G |

1G BiDi SFP |

Enterprise access, campus networks |

| 10G |

10G BiDi SFP+ |

Data center interconnect, aggregation |

| 25G |

25G BiDi SFP28 |

High-speed access and edge networks |

| 40G / 100G |

BiDi QSFP (less common) |

Advanced metro and carrier networks |

Among these, 1G and 10G single fiber SFPs are the most widely deployed, as they strike a balance between performance, cost, and compatibility with existing network equipment.

Types by Transmission Distance

Transmission distance is another critical factor when selecting a single fiber SFP. Longer distances require higher optical power and tighter link budget control.

| Distance |

Typical Wavelength Pair |

Common Applications |

| 10km |

1310nm / 1550nm |

Campus and short metro links |

| 20km |

1310nm / 1550nm or 1490nm / 1550nm |

Enterprise and ISP access |

| 40km |

1490nm / 1550nm |

Metropolitan area networks |

| 80km+ |

CWDM wavelengths |

Long-haul and carrier-grade networks |

As transmission distance increases, factors such as fiber quality, splice loss, and connector cleanliness become more important. Longer-reach single fiber SFPs are typically used in telecom or metro networks where fiber resources are scarce but distances are significant.

Types by Wavelength Pairing

Single fiber SFPs always operate in complementary wavelength pairs, which defines how they are deployed at each end of the link.

| Local TX / RX |

Remote TX / RX |

Notes |

| TX 1310nm / RX 1550nm |

TX 1550nm / RX 1310nm |

Most common BiDi pairing |

| TX 1490nm / RX 1550nm |

TX 1550nm / RX 1490nm |

Used for longer distances |

| CWDM pairs |

Corresponding CWDM pairs |

Supports dense wavelength planning |

Correct wavelength pairing is essential for link establishment. When planning a network, engineers must ensure that each single fiber SFP on one end has a properly matched counterpart on the opposite end.

Overall, the wide variety of single fiber SFP module types makes them suitable for everything from simple enterprise links to complex metropolitan and carrier networks. Understanding these classifications helps narrow down the options and prevents compatibility or performance issues later in deployment.

➡️ Common Applications of Single Fiber SFP

Thanks to their ability to transmit and receive data over a single strand of fiber, single fiber SFP modules are widely used in networks where fiber resources are limited, expensive, or difficult to deploy. Their flexibility makes them suitable for a broad range of applications across enterprise, telecom, and service provider environments.

Metropolitan Area Networks (MAN)

Single fiber SFPs are commonly deployed in metropolitan area networks, where fiber infrastructure often spans long distances and leasing costs are high. By reducing fiber usage by 50%, network operators can significantly lower operational expenses while maintaining reliable high-speed connectivity between buildings, campuses, or city-wide network nodes. Long-reach single fiber SFPs (40km or 80km) are especially valuable in these scenarios.

Telecom and ISP Access Networks

In telecom and ISP access networks, fiber availability is often constrained at the access layer. Single fiber SFP modules are widely used in FTTB (Fiber to the Building) and FTTC (Fiber to the Curb) deployments, where efficient fiber utilization is critical. Their bidirectional design aligns well with point-to-point access links, enabling service providers to scale their networks without extensive new fiber construction.

Enterprise Campus Networks

Large enterprise campuses frequently rely on fiber links to connect multiple buildings or remote offices. In such environments, single fiber SFPs allow IT teams to extend network coverage using existing fiber infrastructure, avoiding costly re-cabling projects. For 1G and 10G links between access and aggregation switches, single fiber SFPs provide a cost-effective and future-ready solution.

Data Center Interconnection (DCI)

While dual fiber SFPs are still common inside data centers, single fiber SFPs are increasingly used for data center interconnection—especially when connecting separate facilities over longer distances. In cases where dark fiber availability is limited, single fiber SFPs help maximize link density and simplify fiber management between sites.

Industrial and Smart Infrastructure Networks

Single fiber SFPs are also used in industrial automation, transportation systems, and smart city infrastructure. These environments often involve long outdoor fiber runs and challenging installation conditions. Reducing fiber count not only lowers material costs but also improves deployment efficiency and reliability in harsh or remote locations.

Summary: Across all these scenarios, the common theme is efficient fiber utilization without sacrificing performance. Whether in a city-wide network or a private enterprise deployment, single fiber SFPs provide a practical solution for extending network reach while controlling costs.

➡️ Advantages of Using Single Fiber SFP

The growing adoption of single fiber SFP modules is driven by a set of clear and practical advantages. While their technical foundation lies in bidirectional transmission, the real value of single fiber SFPs becomes evident when viewed from a network design and operational perspective.

Efficient Fiber Utilization

One of the most significant advantages of using a single fiber SFP is its ability to reduce fiber consumption by 50%. By transmitting and receiving data on a single strand of fiber, organizations can double the number of links supported by existing fiber infrastructure. This is especially beneficial in environments where fiber is scarce, leased, or difficult to install.

Lower Deployment and Expansion Costs

Because fewer fibers are required, single fiber SFPs help reduce the overall cost of network deployment. This includes savings on fiber cabling, patch panels, splicing, and long-term maintenance. When expanding an existing network, single fiber SFPs often eliminate the need for new fiber runs, making upgrades faster and more cost-effective.

Full-Duplex Performance Without Trade-Offs

Despite using only one fiber, single fiber SFPs deliver full-duplex communication with the same bandwidth, latency, and reliability as dual fiber SFP modules. Whether operating at 1G or 10G, there is no performance penalty for choosing a single fiber solution when it is properly deployed.

Ideal for Fiber-Limited Environments

In metropolitan, telecom access, and remote enterprise networks, fiber availability is often the main constraint. Single fiber SFPs provide a practical workaround by maximizing the value of existing fiber assets. This makes them particularly attractive for service providers and organizations planning long-term network scalability.

Seamless Integration With Standard Network Equipment

Most single fiber SFP modules are designed to be MSA-compliant, allowing them to work seamlessly with standard Ethernet switches, routers, and media converters. From the device perspective, they behave just like traditional SFPs, requiring no special configuration beyond proper wavelength pairing.

To sum up: Taken together, these advantages explain why single fiber SFPs are increasingly chosen for modern fiber networks. However, like any optical solution, they also come with specific considerations that must be understood before deployment.

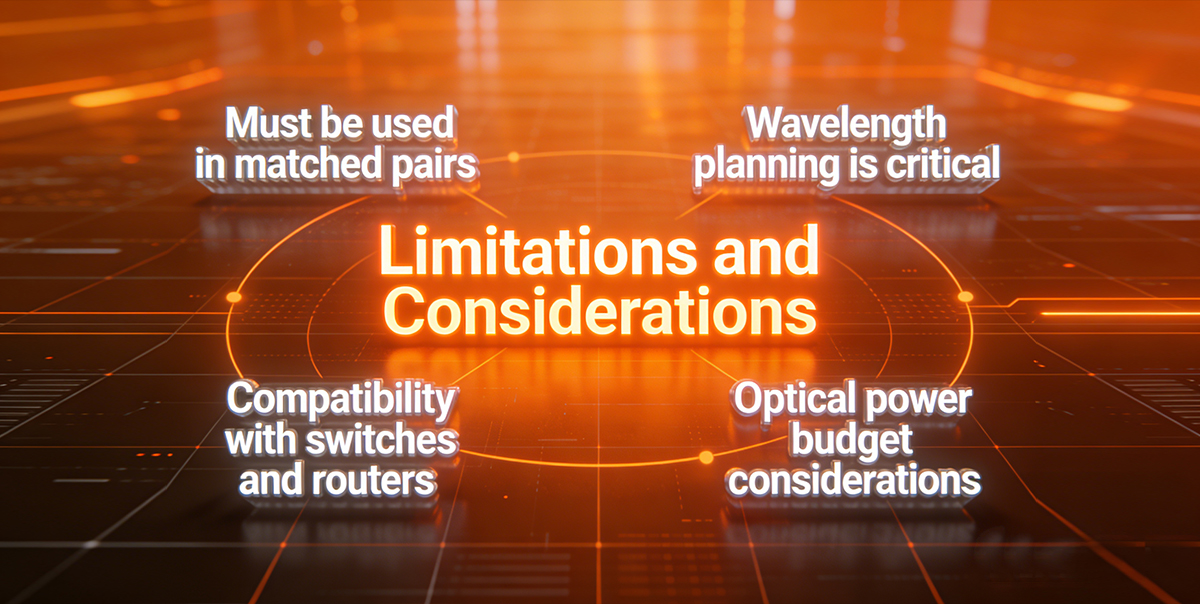

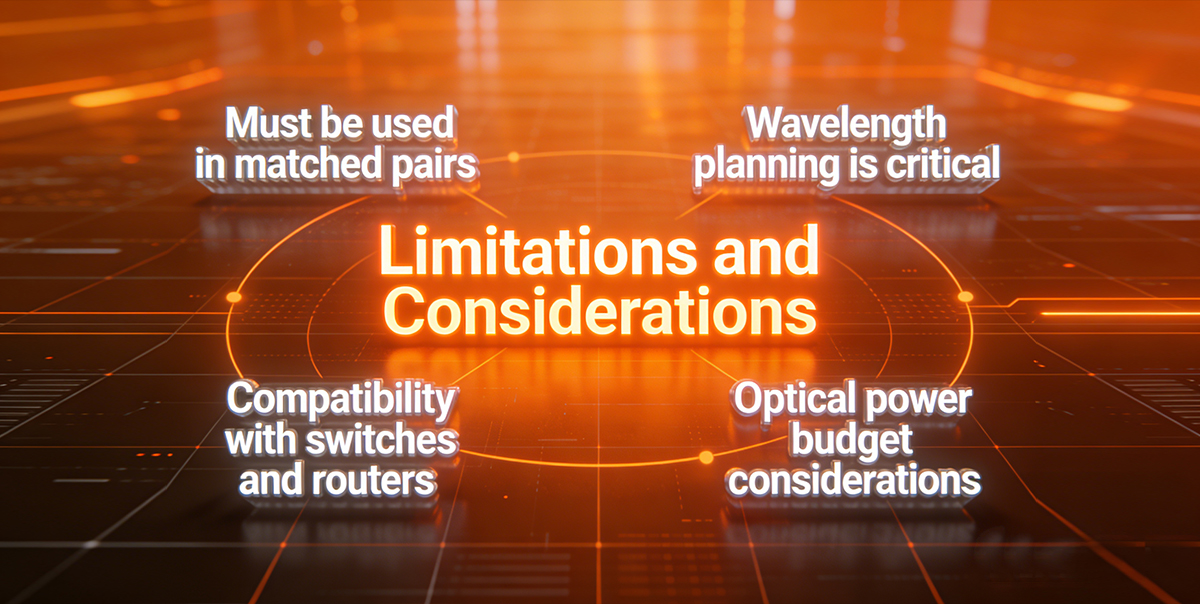

➡️ Limitations and Considerations

While single fiber SFP modules offer clear benefits in fiber efficiency and cost savings, they are not a universal solution for every network scenario. Understanding their limitations and deployment considerations is essential to avoid compatibility issues and ensure stable long-term operation.

Requires Matched Wavelength Pairs

One of the most important considerations when using single fiber SFPs is that they must be deployed in complementary pairs. Each link requires two modules with opposite transmit and receive wavelengths. Installing two identical single fiber SFPs on both ends of a link will prevent communication. Proper labeling and wavelength planning are therefore critical, especially in large-scale networks.

More Demanding Optical Planning

Because single fiber SFPs rely on precise wavelength separation, factors such as optical power budget, insertion loss, and connector quality play a more significant role—particularly over long distances. Dirty connectors or excessive splice loss can have a greater impact on link stability compared to short-reach dual fiber deployments.

Limited Use With Multimode Fiber

Most single fiber SFP modules are designed for single-mode fiber (SMF) and are not compatible with multimode fiber. This limits their use in short-range, multimode-based environments such as some legacy data centers, where dual fiber multimode SFPs may be more practical.

Compatibility and Vendor Support

Although many single fiber SFPs are MSA-compliant, not all network devices support BiDi optics equally well. Some switches or routers may require specific firmware versions or vendor-approved modules. Verifying compatibility in advance is especially important when using third-party single fiber SFPs in branded network equipment.

Inventory and Management Complexity

Compared to dual fiber SFPs, single fiber SFPs introduce additional complexity in inventory management. Since A-end and B-end modules are not interchangeable, maintaining correct stock levels and avoiding mix-ups becomes an operational consideration for network teams.

In summary, single fiber SFPs deliver substantial advantages when deployed correctly, but they require more careful planning and management than traditional dual fiber solutions. Recognizing these considerations helps ensure that the benefits outweigh the challenges.

➡️ How to Choose the Right Single Fiber SFP

Choosing the right single fiber SFP requires more than just matching speed and distance. To ensure compatibility, performance, and long-term reliability, network engineers should evaluate several key factors in a structured way. The following steps provide a practical framework for selecting the correct module for your network.

Step 1: Confirm Network Device Compatibility

Start by verifying that your switch, router, or media converter supports single fiber (BiDi) SFP modules. Check the device’s hardware specifications, supported transceiver list, and firmware requirements. Even when using MSA-compliant optics, some network vendors impose restrictions or require specific firmware versions.

Step 2: Determine Required Speed and Transmission Distance

Next, identify the data rate and link length needed for your application. Common options include 1G and 10G single fiber SFPs, with distances ranging from 10km to 80km or more. Selecting a module with sufficient optical budget is critical—especially for long-distance links where signal loss accumulates.

Step 3: Select the Correct Wavelength Pair

Single fiber SFPs must always be installed in matched wavelength pairs. Determine which wavelength combination is required at each end of the link, such as 1310nm-TX / 1550nm-RX on one side and 1550nm-TX / 1310nm-RX on the other. Proper labeling and documentation help prevent installation errors.

Step 4: Verify Fiber Type and Connector Interface

Ensure that the deployed fiber is single-mode fiber (SMF) and that the connector type (typically LC) matches both the transceiver and patch cords. Using incompatible fiber or connectors can result in link failures or degraded performance.

Step 5: Consider Monitoring and Operational Features

For better visibility and troubleshooting, many single fiber SFPs support Digital Optical Monitoring (DOM). DOM allows real-time monitoring of optical power, temperature, and voltage, which is particularly useful in large or mission-critical networks.

By following these steps, network teams can confidently select single fiber SFP modules that align with both technical requirements and operational constraints. A structured selection process minimizes deployment risks and maximizes the long-term benefits of single fiber technology.

➡️ Are Single Fiber SFPs Compatible with Third-Party Switches?

Compatibility is a common concern when deploying single fiber SFP modules, especially in networks that use branded switches or routers. In most cases, single fiber SFPs are designed to be MSA-compliant, meaning they follow industry standards for form factor, electrical interface, and optical performance. From a technical standpoint, this allows them to function like standard SFPs when installed in compatible ports.

However, real-world compatibility depends on the policies of the network equipment vendor. Some manufacturers restrict the use of third-party optics through firmware checks or vendor-specific coding. In these environments, a single fiber SFP must be properly coded or programmed to match the target device, regardless of whether it is a single fiber or dual fiber module.

From an optical perspective, there is no difference in compatibility requirements between single fiber and dual fiber SFPs. As long as the wavelength pair, speed, and distance specifications are correct, a third-party single fiber SFP can deliver the same performance and reliability as an original branded module.

Many organizations choose third-party single fiber SFPs to reduce costs and increase sourcing flexibility. When doing so, best practices include:

-

Verifying the module is tested and coded for the specific switch model

-

Ensuring firmware versions are compatible

-

Testing modules in a controlled environment before large-scale deployment

When these steps are followed, third-party single fiber SFPs are widely used in enterprise, data center, and service provider networks with excellent results.

➡️ Summary: Is Single Fiber SFP Right for Your Network?

A single fiber SFP is a practical and efficient optical solution designed to maximize fiber utilization without compromising performance. By transmitting and receiving data over a single strand of single-mode fiber using different wavelengths, it offers the same speed and reliability as traditional dual fiber SFPs while significantly reducing fiber requirements.

Single fiber SFPs are especially well suited for environments where fiber resources are limited or costly, such as metropolitan area networks, telecom access networks, enterprise campuses, and long-distance inter-building links. They provide clear advantages in terms of cost control, scalability, and infrastructure efficiency—particularly when network expansion is planned on existing fiber.

However, successful deployment depends on proper planning. Factors such as wavelength pairing, device compatibility, optical budget, and inventory management must be carefully considered. When these requirements are addressed, single fiber SFPs integrate seamlessly into standard Ethernet networks and deliver stable, full-duplex performance.

In short, if your network needs to do more with less fiber, a single fiber SFP is often the right choice. With the correct module selection and deployment strategy, it can become a key component in building a cost-effective, scalable, and future-ready fiber optic network.

➡️ Frequently Asked Questions About Single Fiber SFP (FAQ)

What is the difference between a single fiber SFP and a BiDi SFP?

There is no technical difference between a single fiber SFP and a BiDi SFP. Both terms describe the same type of optical transceiver that transmits and receives data over a single fiber using two different wavelengths. “BiDi SFP” emphasizes the bidirectional transmission method, while “single fiber SFP” highlights the use of one fiber strand.

Do single fiber SFP modules need to be used in pairs?

Yes. Single fiber SFPs must always be deployed in matched wavelength pairs. One module transmits on one wavelength and receives on another, while the module on the opposite end uses the complementary wavelength configuration. Using two identical modules on both ends will prevent the link from working.

Can I mix different brands of single fiber SFPs?

In many cases, yes. As long as the modules are MSA-compliant, use compatible wavelengths, and support the same speed and distance, single fiber SFPs from different vendors can work together. However, compatibility should always be tested—especially when using branded network equipment with vendor restrictions.

Are single fiber SFPs single-mode or multimode?

Single fiber SFPs are almost exclusively designed for single-mode fiber (SMF). They are not typically used with multimode fiber, which is more common in short-distance, dual fiber deployments inside data centers.

Does using a single fiber SFP affect network speed or latency?

No. A single fiber SFP provides the same bandwidth and latency as a dual fiber SFP of the same speed class. A 1G or 10G single fiber SFP delivers full line-rate performance when properly paired and deployed.

What happens if the wavelength pairing is incorrect?

If the wavelength pairing is incorrect, the optical link will fail to establish. The modules will not be able to receive each other’s signals. This is one of the most common causes of issues in single fiber SFP deployments and highlights the importance of correct labeling and planning.

Are single fiber SFPs more expensive than dual fiber SFPs?

Individual single fiber SFP modules may be slightly more expensive than dual fiber SFPs, but the overall system cost is often lower. Savings come from reduced fiber usage, fewer cables, and lower installation and maintenance costs.