An SFP (Small Form-factor Pluggable) is a compact, hot-pluggable transceiver module that allows networking equipment — including switches, routers, servers, and media converters — to support different physical media, such as optical fiber or copper, without replacing the host hardware. This modular approach enhances deployment flexibility, increases port density, and simplifies maintenance compared with fixed, soldered optics.

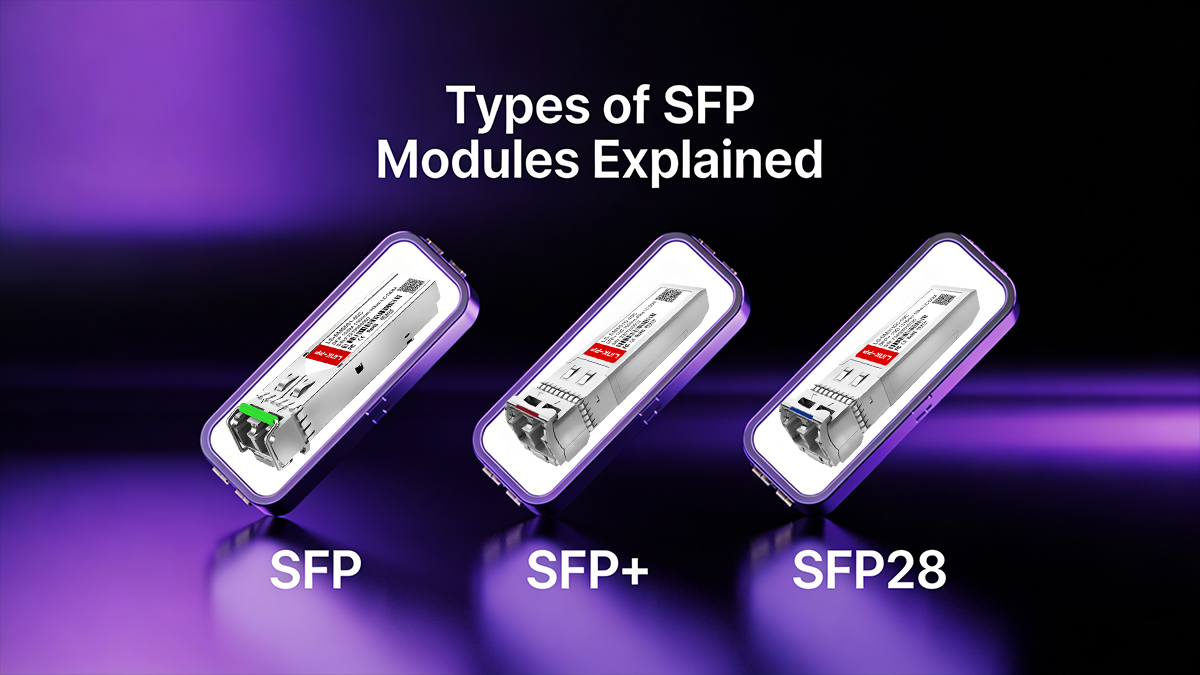

While all SFP family modules share the same mechanical form factor, different members—SFP (1G), SFP+ (10G), and SFP28 (25G)—support different data rates and require specific electrical interfaces. A module may physically fit into a compatible cage, but it will only operate at the intended speed if the host PHY and firmware support that rate.

SFP modules conform to industry multi-source agreements (MSAs) and management interfaces that ensure interoperability. Many modern modules include a standard EEPROM map and support Digital Diagnostic Monitoring (DDM or DOM) defined in SFF-8472, enabling the host device to read module information, temperature, supply voltage, and transmit/receive optical power. Even with MSA compliance and DOM support, full compatibility depends on the host hardware, firmware, and the link standard in use.

What You Will Learn

By reading this guide, you will gain a clear understanding of:

-

The core purpose and function of SFP modules in modern networks.

-

The differences between SFP, SFP+, and SFP28, including supported data rates and electrical requirements.

-

How SFP modules achieve interoperability through MSAs and Digital Diagnostic Monitoring (DDM/DOM).

-

Key specifications such as data rate, media type, reach, and diagnostic capabilities.

-

The advantages of using modular optics over fixed ports.

-

Compatibility considerations, including host hardware, firmware, and link standards.

-

Current standards and use cases for SFP modules in 2026, including server uplinks, data centers, and telecom applications.

⏩ What Is an SFP Module?

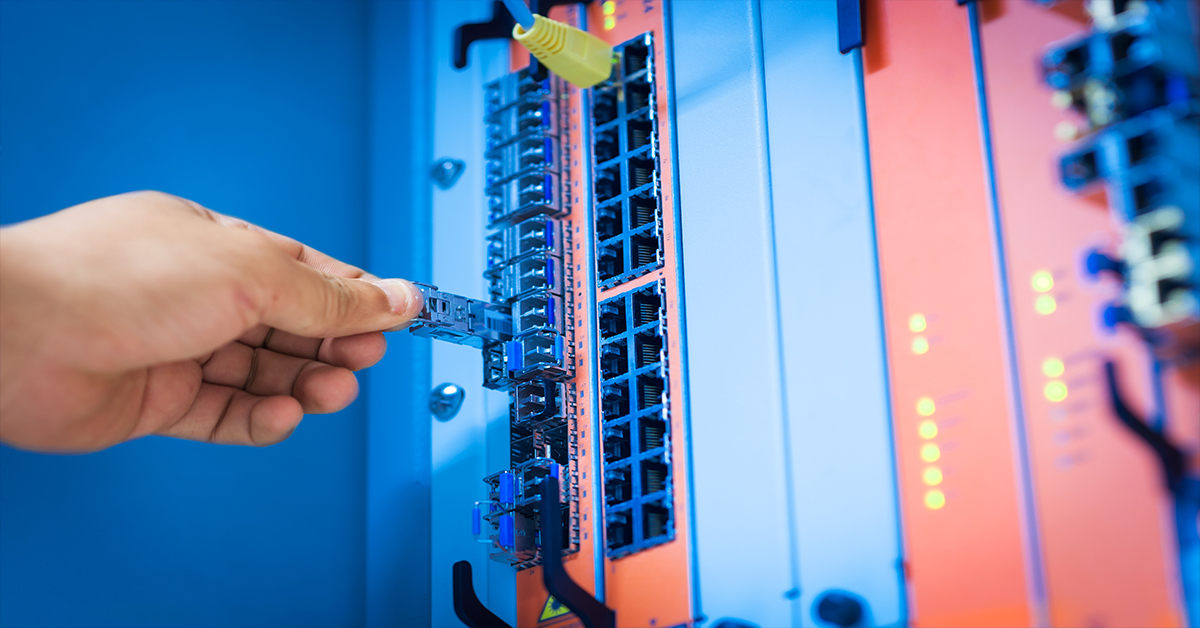

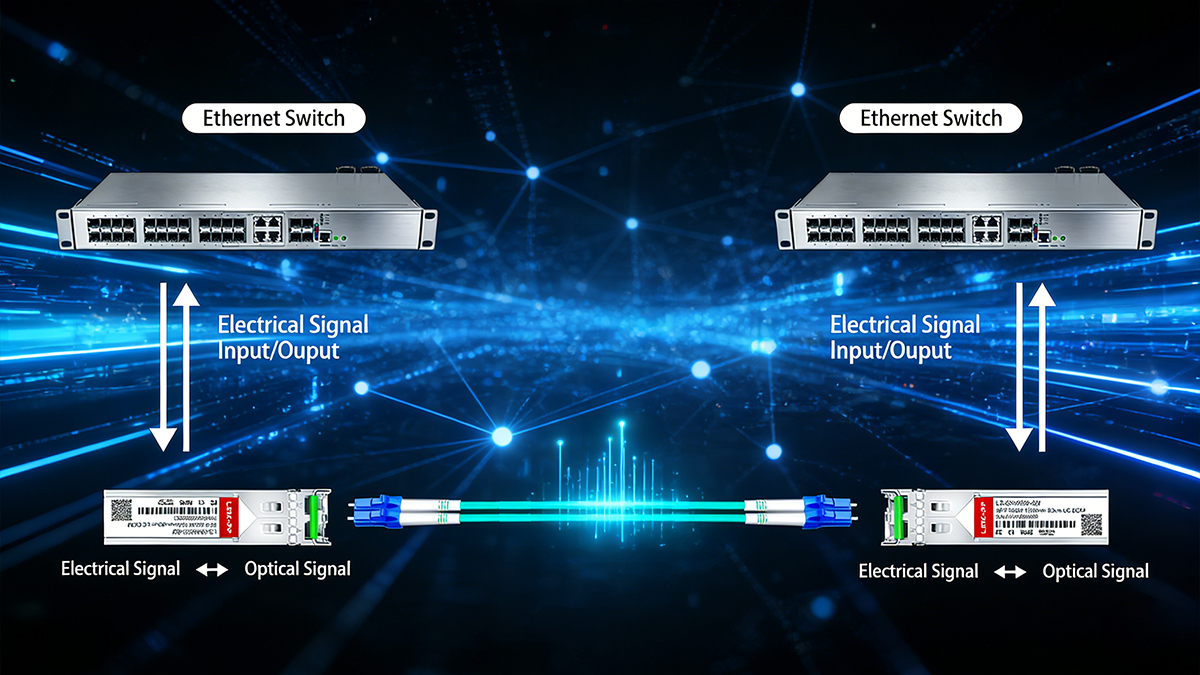

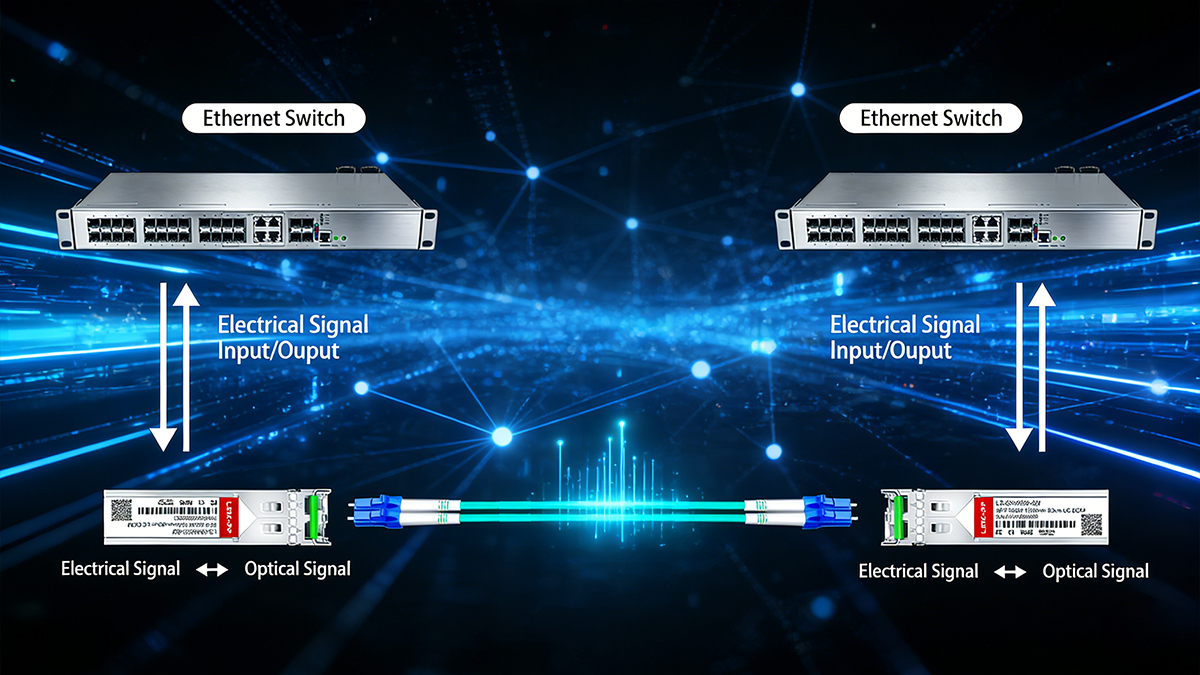

An SFP module (Small Form-factor Pluggable) is a removable, standardized transceiver that plugs into an SFP cage or slot on networking devices such as switches, routers, server NICs, or media converters. Its primary function is to convert between the host device’s electrical signals and the physical transmission medium, which can be either optical fiber or copper cabling.

The SFP form factor was introduced to replace the older GBIC (Gigabit Interface Converter) standard. Early GBIC modules were larger and less space-efficient; the SFP form factor reduced size while retaining hot-pluggability and modular flexibility. This is why SFPs are sometimes historically referred to as “mini-GBIC.”

SFP modules are standardized through multi-source agreements (MSAs) maintained by industry groups. These MSAs define the mechanical, electrical, and operational specifications to ensure broad interoperability across different vendors’ devices.

Core Functions of an SFP Module

SFP modules perform three primary functions in a network:

-

Electrical-to-optical or optical-to-electrical conversion

-

For optical modules, the SFP contains a TOSA (Transmit Optical Subassembly) and ROSA (Receive Optical Subassembly) to handle the fiber signal.

-

For copper SFP modules (RJ-45), the module integrates the necessary PHY and magnetics to convert electrical signals to Ethernet over twisted pair.

-

Standardized interface with host devices

-

The module connects to the host via a defined pinout and electrical interface.

-

Communication with the host includes management and monitoring capabilities via the I²C interface and EEPROM, allowing the host to read module information such as vendor, part number, supported speed, and diagnostics.

-

Support for Digital Diagnostic Monitoring (DDM/DOM)

-

Many SFP modules support SFF-8472-compliant diagnostics, which expose module parameters including temperature, supply voltage, TX/RX power, and bias current.

-

This feature enables network administrators to monitor link health and preemptively identify issues without physically inspecting the module.

SFP vs. GBIC – Why SFP Became the Standard

| Feature |

GBIC |

SFP |

| Form factor |

Larger |

Compact, 1/2 the size of GBIC |

| Hot-pluggable |

Yes |

Yes |

| Port density |

Lower |

Higher |

| Data rate support |

Up to 1 Gbps |

1 Gbps (SFP), 10 Gbps (SFP+), 25 Gbps (SFP28) |

| Interoperability |

Vendor-dependent |

Standardized via MSA |

The transition from GBIC to SFP allowed for higher port density in switches and routers, while maintaining hot-swappable flexibility and interoperability across different vendors’ equipment. Over time, the SFP form factor evolved into SFP+ and SFP28 to support faster data rates while retaining backward compatibility in many cases.

Key Takeaways

-

SFP modules are removable, standardized optical transceivers that enable modular media deployment.

-

They convert signals between electrical and optical media and can support copper or fiber connections.

-

Standardization through MSAs ensures mechanical and electrical compatibility across vendors.

-

Digital diagnostics (DOM) provide real-time monitoring of module health and link performance.

-

SFP replaced GBIC to improve port density, flexibility, and efficiency in networking equipment.

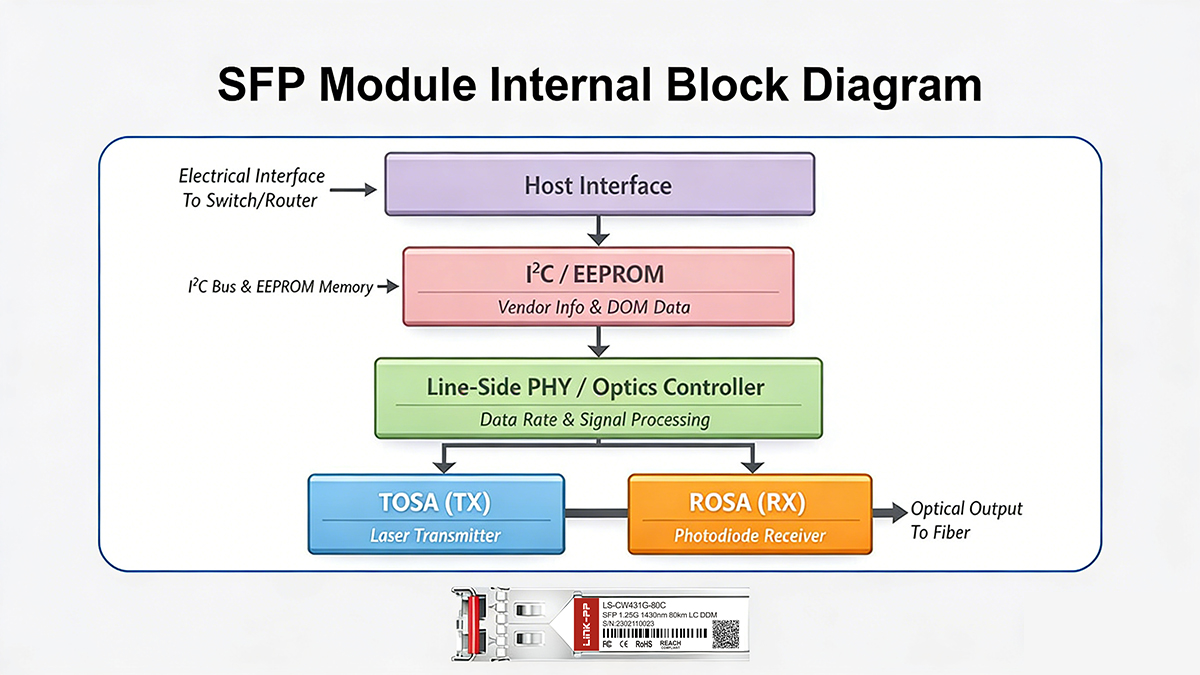

⏩ How Does an SFP Module Work?

An SFP module functions as the bridge between the host device’s electrical signals and the network’s physical medium, whether fiber or copper. Despite their compact size, SFPs integrate several key components that manage signal conversion, link negotiation, and diagnostics.

At a high level, an SFP module contains the following elements:

1. Optical/Electrical Front-End

This front-end ensures proper signal conversion and supports the link standard for which the module is designed (e.g., 1000BASE-LX, 10GBASE-SR, 25GBASE-SR).

2. Line-Side Optics or Electrical PHY

The line-side optics or PHY ensures that the transmitted and received signals comply with the relevant standard. It defines:

-

Data rate compatibility (1G, 10G, 25G)

-

Signal encoding and modulation (e.g., NRZ vs. PAM4)

-

Optical wavelength and launch power for fiber modules

This component is critical because even if a module physically fits into a slot, incorrect PHY or wavelength mismatch can prevent the link from negotiating properly.

3. EEPROM and Management Interface

SFP modules include a 256-byte EEPROM with an I²C interface that stores:

-

Vendor and part number

-

Supported speed and media type

-

Cable type and wavelength

-

Diagnostic and operational parameters

Many SFPs implement Digital Optical Monitoring (DOM or DDM) as defined in SFF-8472, which allows the host to monitor:

This real-time monitoring helps administrators detect potential issues before they affect network performance.

4. Host Interface / Pinout

The host interface is the electrical connector that mates with the switch, router, or server slot. Successful operation requires:

-

The host PHY and SFP PHY to support the same speed and standard

-

Agreement on the management and diagnostics interface

-

Proper electrical signaling to negotiate link parameters automatically

Without this compatibility, the module may not initialize correctly or may operate at a lower data rate.

Practical Notes

-

Most modern SFPs provide hot-swappable operation, allowing installation or replacement without powering down the host device.

-

Digital diagnostics (DOM) not only provide module health information but can also support link troubleshooting, such as identifying fiber degradation or misaligned connections.

-

Module firmware and host firmware may impose additional constraints; always verify vendor compatibility matrices when deploying third-party optics.

Suggested Illustration

This diagram illustrates how signals flow from the host to the physical medium and how the EEPROM provides management and diagnostics information.

⏩ Types of SFP Modules Explained

SFP modules are available in a wide range of variants to support different data rates, fiber types, wavelengths, and deployment scenarios. While they share a common mechanical form factor, their internal design and performance characteristics vary significantly depending on the intended application.

| Classification |

Key Options |

Typical Use Cases |

| Data rate |

SFP / SFP+ / SFP28 |

1G, 10G, 25G Ethernet |

| Fiber & reach |

SR / LR / ER |

Data center, campus, metro |

| Wavelength |

BiDi / CWDM / DWDM |

Fiber optimization, carrier networks |

| Media |

Fiber / Copper (RJ-45) |

Flexible deployment options |

Understanding these categories helps ensure the correct module is selected for a given network environment.

By Performance (SFP Family)

The most common way to classify SFP modules is by supported data rate, which directly determines host compatibility and typical use cases.

① SFP (1G)

Standard SFP modules are designed for data rates up to 1 Gbps and are widely used for Gigabit Ethernet applications such as:

These modules are commonly found in enterprise access switches, campus networks, and legacy server uplinks. Despite their age, 1G SFPs remain widely deployed due to their stability, low power consumption, and broad compatibility.

② SFP+ (10G)

SFP+ modules maintain the same physical dimensions as standard SFPs but are engineered for 10 Gbps operation. Typical standards include:

Compared with SFP, SFP+ relies more heavily on the host device for signal processing, which reduces module complexity and power consumption. Many SFP+ modules support SFF-8472 Digital Diagnostic Monitoring, enabling real-time visibility into optical performance.

SFP+ is widely used for data center access, aggregation layers, and high-speed enterprise uplinks.

③ SFP28 (25G)

SFP28 modules extend the SFP form factor to support 25 Gbps signaling, commonly used for:

SFP28 has become the preferred choice for server-facing links and high-density access in modern data centers. While SFP28 modules are mechanically compatible with SFP+ cages, full 25G operation requires SFP28-capable host hardware and firmware. In some environments, an SFP28 module may operate at a lower speed if the host only supports 10G.

By Fiber Type and Reach

SFP modules are also classified by the fiber type and transmission distance they support.

① SR (Short Reach)

-

Designed for multimode fiber (MMF)

-

Typical reach: up to 100–300 meters, depending on fiber grade

-

Common wavelengths: 850nm

SR modules are widely used for short, high-density connections within data centers and equipment rooms.

② LR (Long Reach)

-

Designed for single-mode fiber (SMF)

-

Typical reach: up to 10km

-

Common wavelength: 1310nm

LR modules are commonly deployed in campus networks and building-to-building links.

③ ER (Extended Reach)

-

Single-mode fiber optics for long-distance links

-

Typical reach: 40 km or more

-

Common wavelength: 1550nm

ER modules are used in metro and long-haul enterprise or carrier networks where extended reach is required.

By Wavelength and Special Functions

Some SFP modules are designed to optimize fiber usage or support wavelength-based network architectures.

① BiDi (Bidirectional) SFP Modules

BiDi SFP transmits and receives signals over a single fiber strand by using different wavelengths for upstream and downstream traffic.

Key advantages include:

BiDi modules must be deployed in matched pairs with complementary wavelengths.

② CWDM and DWDM SFP Modules

These modules are typically used in carrier, metro, and backbone networks where maximizing fiber capacity is critical.

By Transmission Medium (Fiber vs. Copper)

From a physical connectivity perspective, SFP modules can be broadly divided into fiber-based SFPs and copper-based SFPs, depending on the transmission medium they interface with.

① Fiber SFP Modules

Fiber SFP modules use optical fiber as the transmission medium and are the most common SFP type in enterprise, data center, and telecom networks. They support a wide range of distances and applications by varying fiber type and wavelength.

Common fiber SFP categories include:

-

SR (Short Reach) — multimode fiber modules for short-distance links, typically within racks or buildings

-

LR / ER — single-mode fiber modules for long-distance transmission across campuses or metro networks

-

BiDi (Bidirectional) — single-fiber solutions using different wavelengths for transmit and receive

-

CWDM / DWDM — wavelength-multiplexed SFPs designed for carrier-grade and high-capacity optical networks

Fiber SFPs are preferred where long distance, low latency, EMI immunity, or high port density are required.

② Copper SFP Modules (RJ-45)

Copper SFP modules, commonly referred to as RJ45 SFP, integrate an Ethernet PHY and magnetics inside the SFP form factor and terminate with a standard RJ-45 port. They allow SFP cages to connect directly to twisted-pair copper cabling (Cat 5e / Cat 6).

Key characteristics of copper SFP modules include:

-

Typically support 10/100/1000BASE-T (and in some cases 2.5G/5G) Ethernet standards

-

Maximum cable length is usually up to 100 meters, depending on speed and cable quality

-

Higher power consumption and heat dissipation compared to fiber SFPs

-

Useful for short-distance links, legacy copper infrastructure, or mixed-media environments

Copper SFPs are often used for management ports, access-layer connections, or gradual migration scenarios, where deploying new fiber is impractical.

⏩ Common SFP Module Specifications

When selecting an SFP module, engineers and buyers typically compare a consistent set of technical specifications. Understanding what each parameter means—and why it matters—helps ensure compatibility, stable links, and predictable performance.

Below are the most commonly searched and evaluated SFP specifications.

Data Rate (Gbps)

The data rate defines the nominal link speed supported by the module, such as 1G SFP, 10G SFP+, or 25G SFP28.

This value must match both the host port capability (switch, router, NIC) and the network standard being deployed.

A higher-rated module will not operate at full speed if the host only supports a lower data rate, and some hosts may reject unsupported modules entirely.

Media Type and Connector

This specification indicates how the SFP physically connects to the cable:

-

Single-mode fiber (SMF) with LC connector

-

Multimode fiber (MMF) with LC connector

-

Single-fiber BiDi optics, using different wavelengths for transmit and receive

-

Copper (RJ-45) SFPs, terminating directly to twisted-pair Ethernet cabling

Media type is usually one of the first filters users apply, as it must align with the existing cabling infrastructure.

Wavelength (nm) and Optical Power Budget

The operating wavelength (for example, 850 nm, 1310 nm, or 1550 nm) defines the optical window used for transmission.

Together with transmitter output power and receiver sensitivity, it determines the optical power budget.

Power budget is a critical factor in answering common questions such as:

Insufficient power budget can result in unstable links or failure to establish a connection.

Maximum Reach (Distance)

Maximum reach specifies the supported transmission distance, typically expressed in meters or kilometers (e.g., 300 m, 10 km, 40 km).

This value is not universal—it depends on:

-

Fiber type (single-mode vs. multimode)

-

Optical standard (SR, LR, ER, etc.)

-

Cable quality and total link loss

Users frequently search by reach first, especially for campus links, building interconnects, or long-haul connections.

DDM / DOM Support (SFF-8472)

Digital Diagnostic Monitoring (DDM), also called Digital Optical Monitoring (DOM), indicates whether the SFP supports real-time operational metrics via the I²C interface defined in SFF-8472.

When supported, the host system can read:

DDM is widely used for link monitoring, preventive maintenance, and troubleshooting, and is often a required feature in enterprise and carrier environments.

Form Factor and MSA Compliance

Form factor identifies whether the module follows SFP, SFP+, or SFP28 mechanical and electrical definitions.

Compliance with relevant MSA (Multi-Source Agreement) standards ensures interoperability across vendors.

While many modules share similar physical dimensions, full performance and stability depend on proper electrical and protocol compatibility between the SFP module and the host hardware.

⏩ What Are SFP Modules Used For?

SFP modules are widely used across enterprise, data center, and telecom networks because they allow a single hardware platform to support multiple link types, distances, and speeds. By selecting the appropriate SFP module, network designers can adapt the same switch or router to different deployment scenarios without changing the base hardware.

Below are the most common and practical use cases for SFP modules in modern networks.

Server Uplinks and Switch Ports

One of the most common applications for SFP modules is server uplinks and switch access ports. Devices equipped with SFP, SFP+, or SFP28 slots can be configured with:

-

Single-mode fiber for longer reach

-

Multimode fiber for short-range, high-density connections

-

Copper RJ-45 SFPs where structured cabling is already in place

This modularity allows organizations to deploy the same switch model across different environments and simply change the transceiver to match media type, distance, or speed requirements. As a result, inventory complexity and upgrade costs are reduced.

Campus and Building Interconnects

SFP optical modules are commonly used to connect wiring closets, floors, or separate buildings within a campus network. Fiber-based SFPs are particularly well suited for these links because they support:

-

Longer distances than copper Ethernet

-

Immunity to electromagnetic interference

-

Higher reliability over outdoor or inter-building runs

Single-mode SFP Transceivers are often selected for building-to-building links, while multimode SFPs are used for shorter distances within the same facility.

Data Center Access and Top-of-Rack (ToR) Uplinks

In data centers, SFP modules play a key role in access-layer and top-of-rack (ToR) switching. Typical deployments include:

These modules are widely used in leaf–spine architectures, where high port density, predictable latency, and efficient cabling are essential. The small form factor of SFP+ and SFP28 allows data centers to scale bandwidth while minimizing power consumption and rack space.

Carrier, Telecom, and Mobile Fronthaul Networks

SFP modules are also widely deployed in carrier and telecom environments, including:

In mobile networks, especially in some 4G and 5G fronthaul scenarios, SFP-based optics are used to connect centralized units (CU) and distributed units (DU). Their compact size, hot-swappable design, and support for standardized optical interfaces make them well suited for dense, field-deployed systems where uptime and serviceability are critical.

Summary of Typical SFP Use Cases

| Network Environment |

Typical Application |

Common SFP Types |

| Enterprise access |

Server uplinks, switch ports |

SFP, SFP+, RJ-45 SFP |

| Campus networks |

Building and closet interconnects |

SFP (SMF/MMF) |

| Data centers |

ToR uplinks, leaf–spine fabrics |

SFP+, SFP28 |

| Telecom & mobile |

OLTs, fronthaul links |

SFP, SFP+, SFP28 |

⏩ Are SFP Modules Hot-Swappable?

Yes. SFP modules are designed to be hot-pluggable, meaning they can be inserted or removed while the host device (switch, router, or NIC) remains powered on—as long as the host platform supports hot swapping.

Most enterprise and carrier-grade devices do support this behavior, but actual operation is governed by the host vendor’s hardware design and firmware policies.

Hot-Swap Risks to Be Aware Of

While hot swapping is common, improper handling can introduce issues such as:

-

Electrostatic discharge (ESD) damaging sensitive optical or electrical components

-

Transient link flaps that may affect live traffic

-

Firmware or compatibility checks temporarily disabling a port after insertion

-

Contamination of optical connectors if dust caps are not managed correctly

These risks are operational rather than design flaws and are typically avoidable.

Hot-Swap Best Practices

To minimize issues during insertion or removal:

-

Follow the host vendor’s documented procedures, especially in production networks

-

Use proper ESD protection when handling modules

-

Remove or insert modules straight and gently, without twisting

-

Keep dust caps on LC connectors until fiber is connected

-

If recommended, administratively disable the port before removal and re-enable it afterward

When handled correctly, hot swapping SFP modules is a safe and routine operation that supports fast maintenance and flexible network changes without downtime.

⏩ SFP Module Compatibility Explained

SFP module compatibility is often misunderstood. While many modules share the same physical shape, successful operation depends on multiple layers of compatibility, not just whether the module fits into the port.

1) Mechanical and Electrical (MSA) Compatibility

SFP, SFP+, and SFP28 modules follow industry Multi-Source Agreements (MSAs) that define the mechanical envelope, cage dimensions, and basic pin assignments. As a result, these modules often physically fit into the same SFP cage.

However, mechanical fit alone does not guarantee operation. The electrical interface and signaling requirements differ by generation, and the host device must support the corresponding electrical PHY to operate the module at its rated speed.

2) Speed and PHY Support

The host’s MAC, PHY, and firmware ultimately determine what speeds are supported.

-

An SFP28 module inserted into an SFP+ port may physically fit, but it will only operate if the host supports backward compatibility and can negotiate a lower speed

-

A 25G SFP28 module cannot force 25G operation on a host designed only for 10G

-

Some hosts support mixed-speed operation, while others strictly enforce port speed profiles

This is why datasheets often note that physical compatibility does not imply performance compatibility.

3) Vendor Firmware Restrictions and EEPROM Coding

Many switch and router vendors implement firmware-level checks that read the module’s EEPROM (vendor name, OUI, part number). In some ecosystems:

-

Third-party modules may trigger warnings or be disabled

-

Only vendor-approved or coded optics are officially supported

-

MSA compliance alone does not guarantee acceptance

Always consult the host vendor’s optics compatibility matrix or verify support through lab testing.

Practical Compatibility Checklist

Before selecting an SFP module—especially a third-party optic—confirm that:

-

The host port supports the required speed and link standard

-

The module is validated by the vendor or proven in your environment

-

Wavelength, fiber type, and connector match the intended link

-

DOM/DDM support aligns with your monitoring and operational needs

Understanding these compatibility layers helps prevent deployment delays, link failures, and unnecessary troubleshooting in production networks.

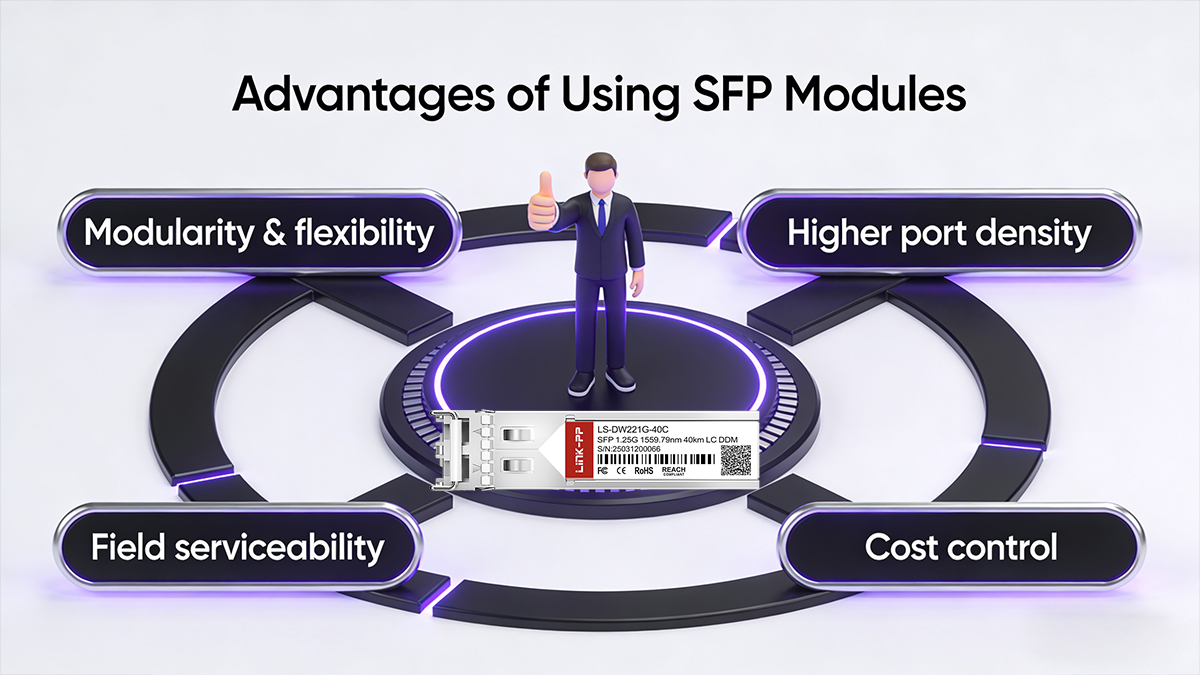

⏩ Advantages of Using SFP Modules

SFP modules remain a foundational building block in modern networks because they balance performance, flexibility, and operational efficiency. Compared with fixed-port designs, they offer several practical advantages.

Modularity and Media Flexibility

SFP-based platforms allow network operators to change the transmission medium without replacing the host hardware. The same switch port can support single-mode fiber, multimode fiber, or copper simply by swapping the module, making it easier to adapt to evolving link requirements.

Higher Port Density and Scalable Bandwidth

The compact SFP form factor enables high port density on switches and routers. Newer variants such as SFP28 deliver 25G bandwidth within the same physical footprint, allowing capacity upgrades without increasing rack space or power footprint.

Improved Serviceability and Monitoring

SFP modules are designed for hot-swappable operation, reducing maintenance downtime. Many optics also support Digital Optical Monitoring (DOM), enabling real-time visibility into temperature, voltage, and optical power—useful for proactive troubleshooting and lifecycle management.

Cost-Efficient Network Design

By selecting optics that match the actual distance, speed, and fiber type, organizations can avoid overprovisioning. This modular approach helps control capital expenditure while still allowing incremental upgrades as network demands grow.

Together, these advantages make SFP modules a practical and future-ready choice for enterprise, data center, and carrier networks.

⏩ SFP Modules in 2026: Standards and Current Use Cases

By 2026, SFP modules continue to play a central role in Ethernet network design, supported by mature standards and well-established deployment patterns across enterprise, data center, and telecom environments.

Standards in Production and Industry Direction

Modern SFP variants are grounded in IEEE 802.3 Ethernet standards and long-standing MSA specifications that define form factor, electrical interfaces, and management behavior.

Key standards shaping current deployments include:

-

IEEE 802.3by (25GbE) — formalized 25G Ethernet, enabling SFP28-based links for server and access-layer connectivity

-

Related 50G and 100G Ethernet task groups — influencing breakout architectures and upstream aggregation, even when SFP28 remains the server-facing optic

-

SFF and CMIS/SFF-8472 management specifications — ensuring consistent monitoring and diagnostics across vendors

Since the mid-2010s, the market trend has steadily shifted toward 25G as the preferred server access speed, offering a practical balance of bandwidth, power efficiency, and port density. At the same time, 10G SFP+ remains widely deployed in access and aggregation layers where upgrade cycles are longer or bandwidth demands are stable.

By 2026, SFP28 is a mainstream choice rather than an emerging technology.

Current and Emerging Use Cases (2026)

Based on observed deployments and vendor roadmaps, SFP modules are commonly used in the following scenarios:

-

Data center leaf–spine architectures

SFP28 modules are widely used for 25G server uplinks, while higher-speed optics are aggregated at the spine. This model simplifies cabling, improves scalability, and aligns with modern NIC capabilities.

-

Edge networks and 5G fronthaul

Compact, hot-swappable fiber SFPs are well suited for space- and power-constrained edge locations, including mobile fronthaul and distributed radio access networks, where operational flexibility is critical.

-

Enterprise network upgrades

Many enterprises continue phased migrations from 1G to 10G and 25G, driven by application growth, server refresh cycles, and improving cost-per-bit economics. SFP-based platforms allow these upgrades without wholesale hardware replacement.

Editorial and Publication Note

When referencing a specific year such as 2026, it is good practice to clearly state:

This improves clarity for readers and reinforces the content’s technical credibility and timeliness.

⏩ SFP vs. Other Transceiver Modules

Choosing the right transceiver form factor depends on bandwidth requirements, port density, and how much flexibility the network design needs. Below is a practical comparison between the SFP family and other common approaches.

SFP Family vs. QSFP / QSFP28

The SFP family (SFP, SFP+, SFP28) is designed for single-lane, point-to-point links, making it well suited for server connections and access-layer ports.

By contrast, QSFP and QSFP28 modules package multiple electrical lanes into a larger form factor:

QSFP-based optics are primarily deployed in aggregation and spine layers, where high-capacity links and breakout configurations are required.

In modern data centers:

-

SFP28 is often preferred for server uplinks, offering 25G per port with high density and lower cost per endpoint

-

QSFP28 is used upstream to aggregate many SFP28 links into fewer high-speed connections

This complementary usage allows efficient scaling without overbuilding bandwidth at the server edge.

SFP Modules vs. Fixed Optical Ports

Some switches and appliances include fixed optical ports, where the transceiver is permanently integrated.

-

Fixed optics can be cost-effective when the media type and reach are known and unlikely to change

-

However, they lack the flexibility of pluggable SFP modules, which allow changes in fiber type, wavelength, or reach without replacing the entire device

Pluggable SFPs are especially valuable in environments where network requirements evolve over time, or where hardware reuse and phased upgrades are priorities.

In practice, SFP-based designs provide a balance of flexibility, scalability, and operational control that fixed-port solutions cannot easily match.

⏩ FAQs About SFP Modules

Below are answers to common questions that arise during SFP selection, deployment, and troubleshooting.

Q: Can I plug an SFP28 into an SFP+ port and expect 25G?

A: No. While an SFP28 module may physically fit into an SFP+ cage, 25G operation requires explicit host support, including the correct PHY, MAC, and firmware. In many cases, the module will either operate at 10G (if downshifting is supported) or fail to link entirely. Always verify the host vendor’s documentation and compatibility matrix.

Q: What is DOM / DDM and why does it matter?

A: Digital Optical Monitoring (DOM)—also known as Digital Diagnostics Monitoring (DDM)—is defined by SFF-8472 and related specifications. It allows the host to read real-time module metrics such as temperature, supply voltage, laser bias current, and transmit/receive optical power. DOM data helps operations teams detect degrading optics, dirty connectors, or marginal links before failures occur.

Q: Are third-party SFP modules safe to use?

A: Many high-quality third-party SFPs are fully interoperable when they adhere to MSA standards and are properly coded. However, some network vendors enforce firmware-based checks that may restrict or disable non-approved modules. For production environments, confirm support with the host vendor or validate the optics through lab testing before large-scale deployment.

Q: How do I choose between SR, LR, and ER optics?

A: The choice depends on distance, fiber type, and optical budget:

-

SR (Short Reach) — multimode fiber, typically up to ~300 m

-

LR (Long Reach) — single-mode fiber, commonly up to 10 km

-

ER (Extended Reach) — single-mode fiber for longer distances, often tens of kilometers

Always refer to the module datasheet for exact reach limits, as actual performance depends on fiber quality, connectors, and link loss.

⏩ Summary — What You Should Know About SFP Module

hot-pluggable SFP transceivers defined by industry MSAs and remain a core building block in enterprise, data center, and telecom networks. Their standardized form factor enables flexible media choices and scalable upgrades without replacing host equipment.

When selecting an SFP module, focus on the fundamentals: data rate, transmission medium, reach, and host compatibility. For operational environments where visibility and reliability matter, confirm DOM/DDM support and alignment with the relevant IEEE and SFF standards.

Looking ahead to 2026, the ecosystem has largely converged on 25G SFP28 for server-facing links, while 1G and 10G SFPs continue to serve access and aggregation layers with long upgrade cycles. Across all speeds, vendor compatibility policies and firmware behavior remain a critical consideration during deployment planning.

Call to Action

For standards-compliant SFP, SFP+, and SFP28 modules with validated interoperability and consistent quality, visit the LINK-PP Official Store to explore available options and technical resources.

Appendix — Key references used in this article

-

-

Small Form-factor Pluggable (SFP) — overview and MSA context.

-

SFF-8472 (Digital Diagnostic Monitoring) and EEPROM maps.

-

IEEE 802.3by (25GbE) and related task force notes.

-

Vendor technical notes (Cisco) on SFP/SFP+ installation and hot-swap behavior.

-

Market/technical comparisons (SFP, SFP+, SFP28) and practical notes.

Author: LINK-PP Editorial Team (Guest technical Writers — networking hardware & optical transceivers)

Sources & verification: industry MSAs, IEEE standards, Cisco technical notes, SFF specs, vendor product guides (selected citations inline).

Last updated: January 21, 2026