In modern Ethernet infrastructure, the role of SFP in network design is to provide a flexible, modular interface that lets the same host hardware support different media, speeds, and reach requirements. Rather than locking an edge or aggregation switch into fixed copper or fiber ports, SFP modules enable operators to swap transceivers to match link distance, fiber type, or copper cabling without replacing the entire chassis — a decisive advantage for scalable, cost-effective deployments.

Beyond basic media conversion, SFPs play operational roles that matter to engineering teams: they simplify inventory and spare-parts management, enable hot-swappable maintenance with minimal downtime, and centralize compatibility decisions at the transceiver level (MSA-compliance being the common industry baseline). For network architects, framing SFPs as both a physical interface and a lifecycle management tool helps prioritize design choices that reduce total cost of ownership while preserving flexibility.

This guide explains the practical role of SFP in network environments: how SFP modules function, how they differ from fixed connectors like RJ45, and how to apply SFP choices to real network problems — from short-reach access links to aggregation and campus backbone design. It’s written for engineers and IT decision-makers who need clear, actionable guidance (including how to read datasheets, evaluate DOM telemetry, and verify compatibility) rather than abstract theory.

1️⃣ What is SFP?

SFP (Small Form-factor Pluggable) is a compact, hot-pluggable transceiver module used to convert between a network device’s internal electrical signal and the external physical medium (fiber or copper). In the context of SFP in network design, an SFP is the physical building block that lets a single device port be configured for different media, distances and speeds simply by changing the module.

key Characteristics

-

Form factor & interoperability: SFP is an industry form factor governed by Multi-Source Agreements (MSAs). MSAs define mechanical dimensions, electrical interfaces and management registers so compliant modules fit standard SFP cages across vendors.

-

Hot-pluggable: Modules can be inserted or removed while the host device is powered, enabling quick maintenance and replacements without downtime.

-

Management interface: SFPs include an EEPROM accessible over I²C that stores vendor/part/serial data and — for DOM/DDM-capable modules — live telemetry (Tx/Rx power, temperature, Vcc, laser bias).

-

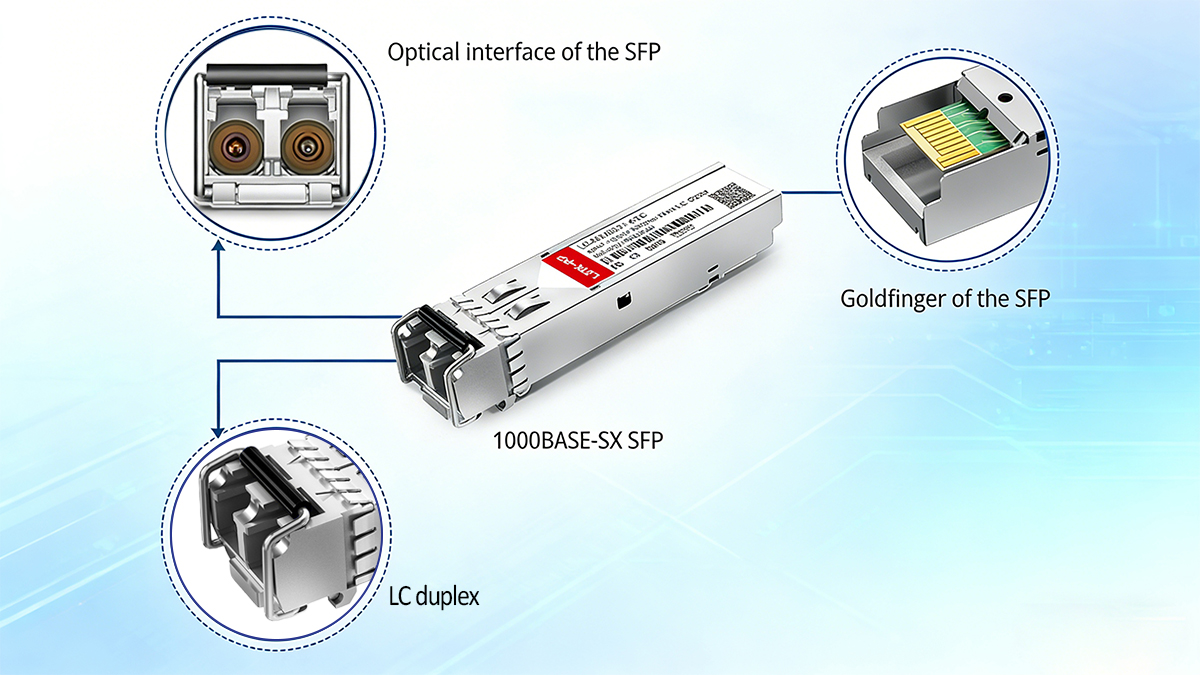

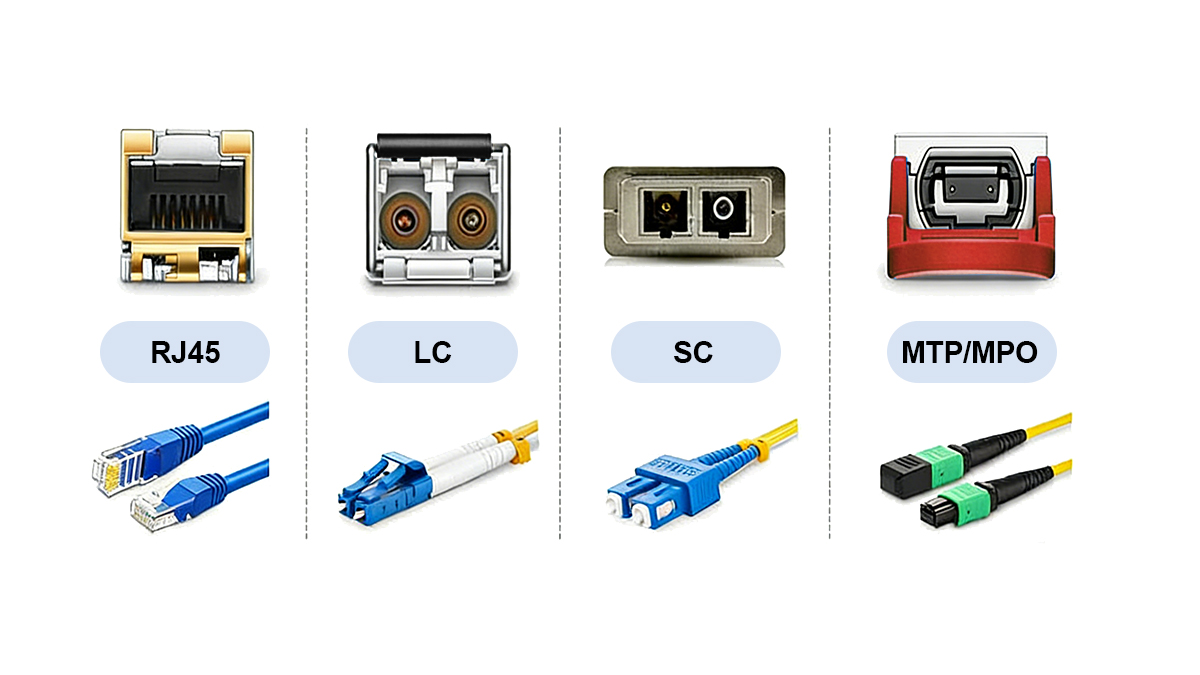

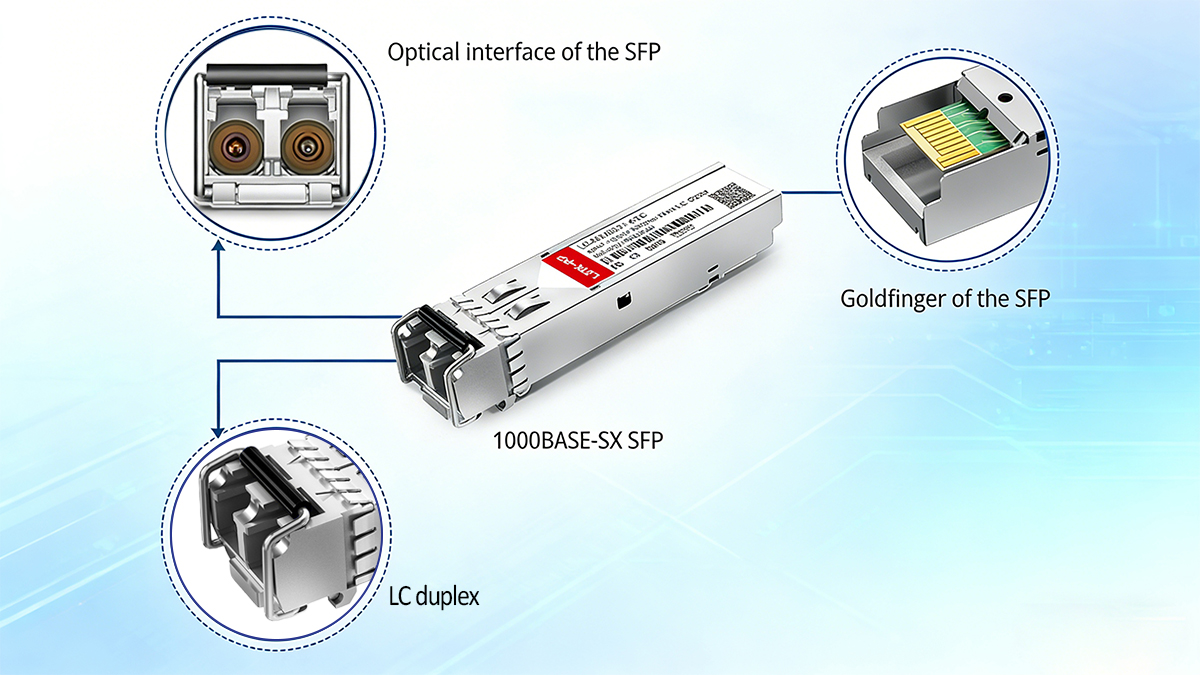

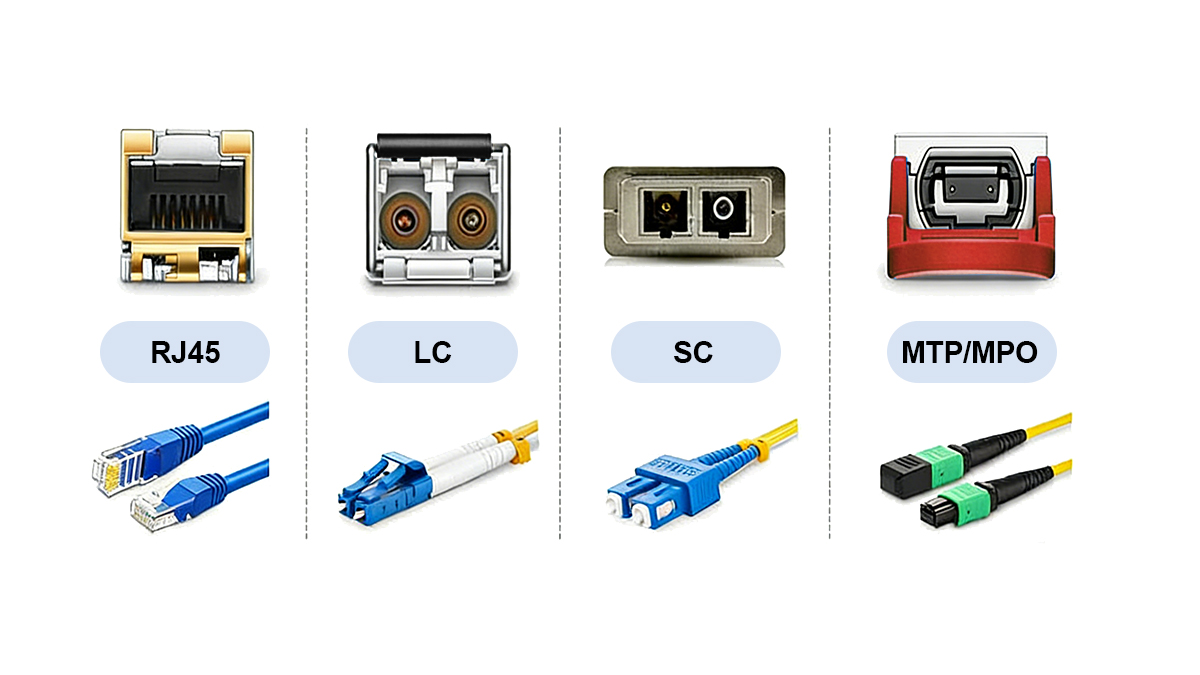

Connector types: Optical SFPs most commonly use LC duplex connectors; copper SFPs expose an RJ45 (8P8C) jack inside the SFP housing.

-

Typical data rates: The classic SFP form factor is widely used for 1 Gbit/s ports; visually identical or similar mechanical cages are used by SFP+ (10 G), SFP28 (25 G) and other high-speed variants, but electrical/thermal requirements differ — always confirm host support.

How an SFP Differs from Related Terms

-

SFP vs SFP+: SFP+ is the 10 Gbit/s-targeted evolution of the form factor. SFP+ modules may fit the same cage but can require different electrical signaling and thermal handling; they are not automatically interchangeable without host support.

-

SFP vs transceiver vs module: These terms are often used interchangeably. “SFP” specifies a particular small pluggable form factor; “transceiver/module” is the generic role (transmit + receive).

-

SFP vs media converters / DACs: SFP modules convert signals at the port level. Direct Attach Copper (DAC) and media converters are alternative solutions for short links or media translation but differ in flexibility, cost and inventory implications.

Common SFP Variants (summary)

-

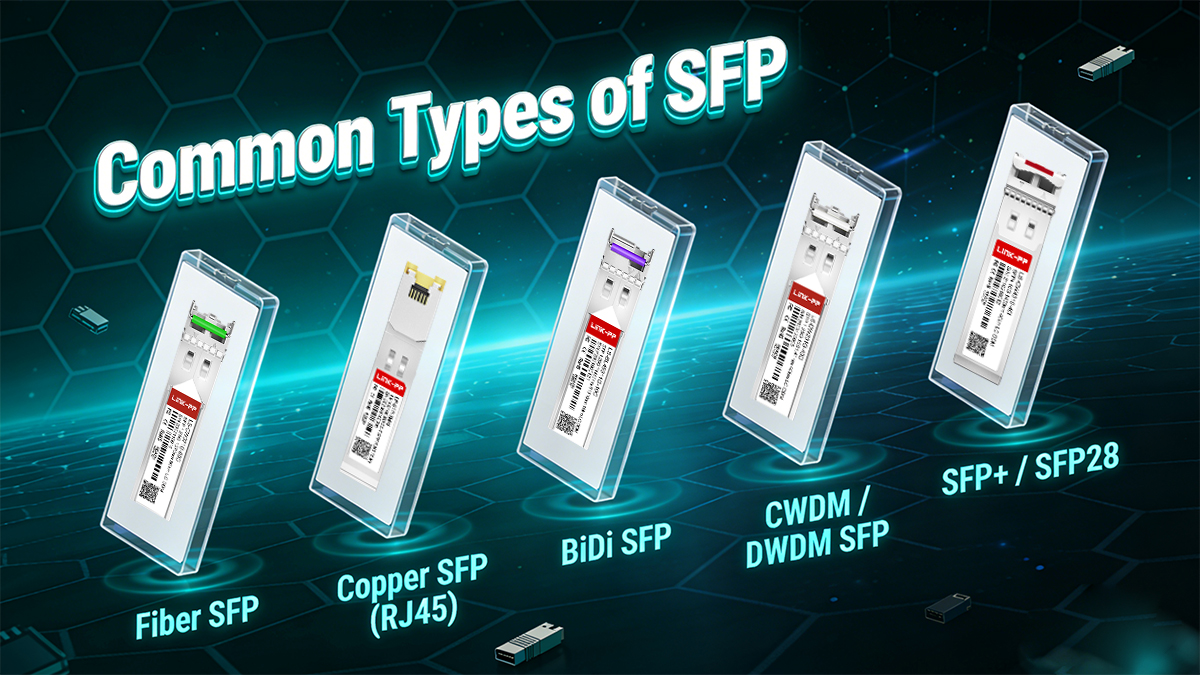

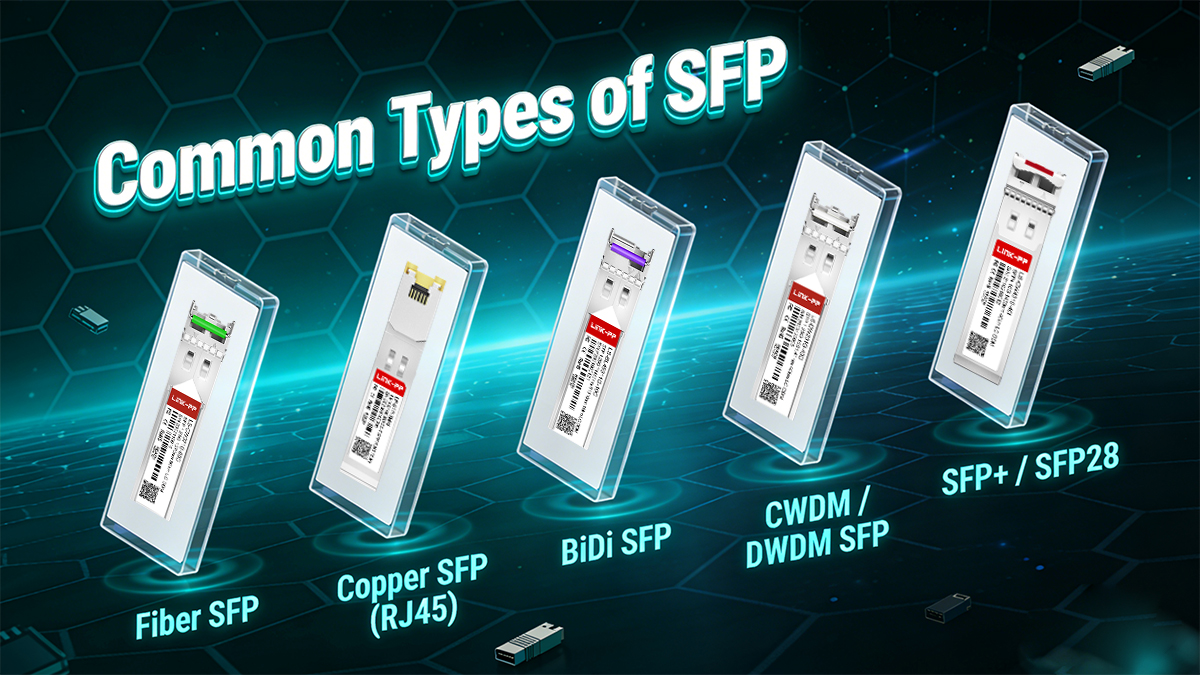

Fiber SFP (SX, LX, ZX, etc.) — used for multimode or single-mode fiber; differ by wavelength, laser type and reach.

-

Copper SFP (RJ45 SFP) — provides 100/1000-Mbit or multi-gig copper via an RJ45 jack in the SFP slot (typical reach ≈100 m).

-

BiDi SFP — single-fibre bidirectional optics, useful when fiber count is constrained.

-

CWDM/DWDM SFP — wavelength-tuned modules for multiplexed metro/long links.

-

Industrial/extended-temp SFP — designed for harsh environments.

Notes

-

Always read the datasheet. Datasheets list supported data rates, wavelengths, Tx/Rx power, receiver sensitivity and temperature range — the true source for design decisions.

-

Check host compatibility. MSA form factor ≠ guaranteed host acceptance; verify vendor compatibility lists or test in a lab.

-

Use DOM telemetry where available. DOM helps baseline and monitor link health post-deployment.

-

Mind optical budget. Calculate optical budget = Tx_min − Rx_sensitivity and compare to estimated link loss with margin.

In short: an SFP is the modular interface that gives a network port its external identity — fiber or copper — and therefore plays a central role in how SFP in network architectures are designed, operated and scaled.

2️⃣ ️The Role of SFP in Network Devices and Ethernet Design

In practical network design, the role of SFP in network devices is to decouple the physical connection from the device hardware itself. Instead of embedding fixed copper or fiber interfaces on a switch, router, or appliance, manufacturers expose a standardized SFP cage and let the transceiver define how that port behaves in the real world.

At a high level, the primary role of an SFP Transceiver is to:

-

Define how signals leave a network device

Internally, network devices process data as electrical signals on their switching or routing ASICs. The SFP module converts those internal signals into the appropriate electrical or optical form required by the external medium. This conversion layer ensures the device can support different physical interfaces without changing its internal design.

-

Determine what transmission medium is used (fiber or copper)

The choice of SFP directly determines whether the link uses optical fiber or twisted-pair copper. A fiber SFP presents an optical interface (commonly LC), while a copper SFP exposes an RJ45 interface. From the device’s perspective, the same port can act as a fiber uplink or a copper Ethernet port purely based on the inserted module.

-

Control how far data can travel

Link distance is governed by the SFP’s optical or electrical characteristics, such as wavelength, transmit power, and receiver sensitivity. These parameters define the supported reach when combined with cable type and quality, making the SFP a key factor in link planning and optical budget calculations.

Network Devices that Rely on SFP Modules

SFP modules are widely used across different types of network equipment, making them a foundational building block in modern Ethernet architectures:

-

Ethernet switches

Deployed in access, aggregation, and core layers, SFP ports allow switches to adapt to different uplink and downlink requirements. Access switches often use SFPs for fiber uplinks, while aggregation and core switches rely on SFP-based interfaces for flexible backbone connectivity.

-

Routers

Routers use SFP ports to connect to WAN, campus, or data center links, enabling the same router model to support various media types and distances depending on deployment needs.

-

Firewalls and security appliances

Security devices frequently use SFP ports to integrate seamlessly into fiber-based network segments or to isolate sensitive links without introducing additional media converters.

-

Network interface cards (NICs)

Servers and appliances equipped with SFP NICs can be deployed with fiber or copper connections as required, which is especially valuable in data centers where cabling standards may vary between racks or zones.

Why SFP Modularity Matters in Real Deployments

By changing the SFP module, a single physical network port can perform entirely different roles—such as a short-reach copper connection, a multimode fiber uplink, or a long-reach single-mode fiber link—without redesigning or replacing the device itself. This modular approach reduces hardware lock-in, simplifies upgrades, and allows network engineers to adapt infrastructure as requirements evolve.

In essence, the SFP transforms a fixed port into a configurable interface, making it one of the most important enablers of flexible, scalable network design.

3️⃣ How Does an SFP Module Work in a Network?

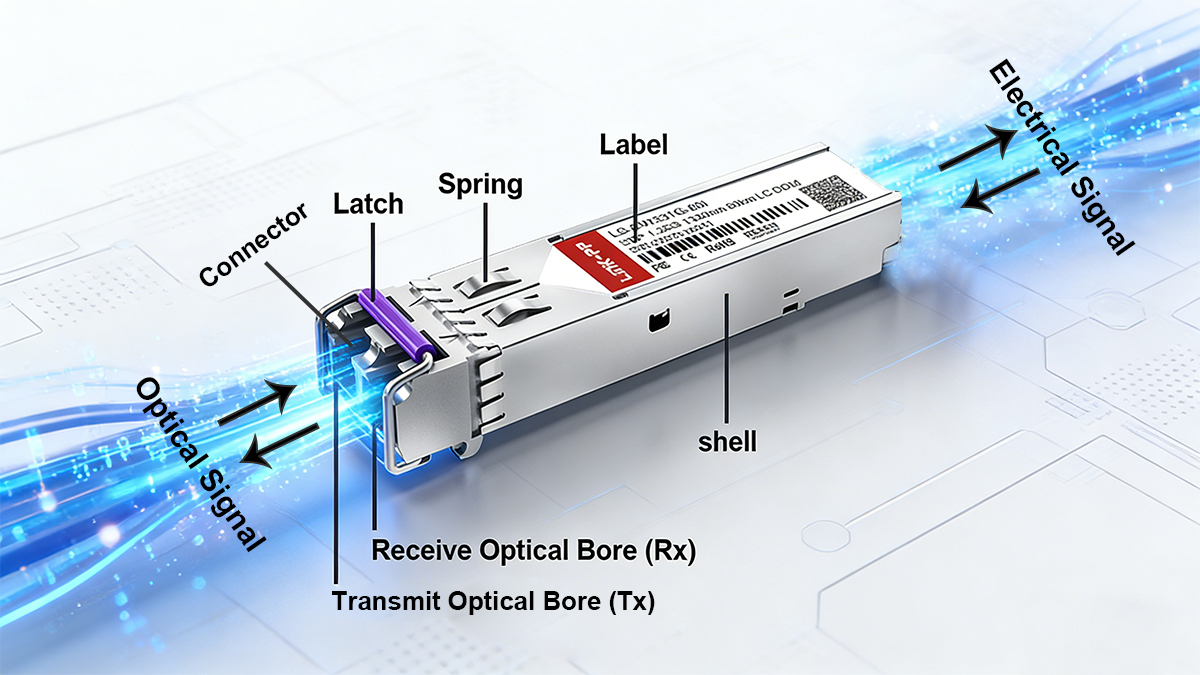

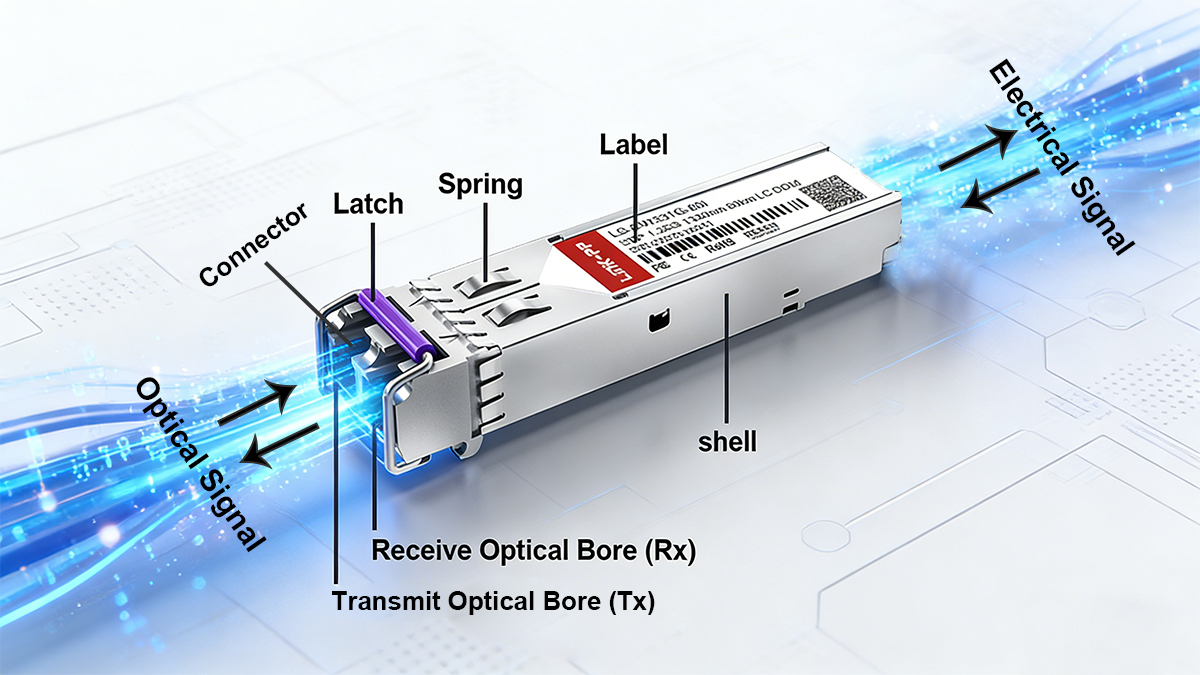

From a functional perspective, the role of an SFP module is signal conversion and adaptation: it stands between the host device’s switching/routing logic and the outside world, translating device-level electrical signals into the physical signalling required by the chosen medium and vice versa.

1. Signal Conversion — the Core Role

At a high level the conversion flow inside a link looks like this:

-

The switch/router ASIC or PHY produces an electrical data stream on the host interface.

-

The SFP receives that stream through the host connector and internal electrical pins.

-

Inside the module the data is converted depending on type:

-

The converted signal is sent over the chosen medium (fiber or copper) to the far-end transceiver, where the reverse conversion happens.

This separation of switching logic and transmission media is an architectural advantage: the device’s forwarding plane doesn’t need per-port hardware changes to support different cable types or distances — the SFP handles the physical specifics.

2. Key Internal Components and Behaviors

An SFP module typically contains a small set of functional blocks:

-

Transmitter and receiver optics/electronics — lasers or LEDs (VCSEL/FP/DFB depending on reach) for fiber, or the PHY and magnetics for copper modules.

-

Clock and data recovery (CDR) where required — to condition and re-time the bit stream for the medium.

-

EEPROM / I²C management interface — a small memory area that stores vendor, part and serial information and (for DOM-capable modules) live telemetry. The host reads this information over a two-wire management bus.

-

Power regulation and protection — to ensure stable Vcc to the optics and protect the host from faults.

-

Thermal/physical packaging — small optics in an MSA-compliant form factor that fits the host cage.

These components together determine behavior such as supported data rate, required bias/current for the laser, and what telemetry (Tx/Rx power, temperature, voltage) the module exposes.

3. Management & Telemetry (DOM / DDM) — Operational Visibility

Many SFPs implement Digital Optical Monitoring (DOM) or Digital Diagnostic Monitoring (DDM). Typical telemetry exposed to the host includes:

-

Transmit power (dBm)

-

Receive power (dBm)

-

Module temperature (°C)

-

Supply voltage (Vcc)

-

Laser bias current (mA)

Hosts poll this data over the module’s management interface (I²C) for monitoring, alarm thresholds, and historical trend analysis. DOM is extremely useful for proactive fault detection (e.g., dirty connectors, drifting power) and for validating optical budgets in the field.

4. Optical vs. copper SFP — Practical Conversion Differences

| Characteristic |

Optical SFP |

Copper (RJ45) SFP |

| Conversion |

Electrical → Optical |

Electrical → Electrical |

| Typical reach |

meters → kilometers |

up to ~100 m |

| Common use |

Uplinks, long-reach links |

Access ports, short links |

| Telemetry |

Often supports DOM |

Limited telemetry (depends on module) |

| Components |

Laser/photodiode, CDR |

PHY, magnetics, jack |

5. Hot-plug Behavior and Link Negotiation

SFPs are designed to be hot-pluggable. When inserted, the host queries the module for identification and capabilities, then configures the port accordingly. Important operational points:

-

Speed/PHY compatibility is governed by the host’s MAC/PHY and the module’s supported rates (e.g., standard SFP Modules are commonly 1G; SFP+ is 10G).

-

Link bring-up is the result of the host and the far-end device both supporting the same medium, encoding and speed. The transceiver itself does not “decide” network-level parameters — it provides the physical layer capability.

-

Some vendors implement firmware checks or vendor-locked lists on hosts; MSA compliance guarantees mechanical/electrical form factor but does not guarantee host acceptance on every platform.

Practical implications for engineers

Because SFPs encapsulate the physical-layer behavior, engineers should treat them as part of the link design rather than interchangeable consumables. Practical recommendations:

-

Verify host compatibility (vendor notes, tested part lists) before deployment.

-

Confirm module datasheet values (wavelength, Tx/Rx power, sensitivity, supported temperatures).

-

Use DOM telemetry to baseline and monitor link health after installation.

-

Plan for optical budget and margin rather than relying on “max reach” marketing numbers.

-

Test with appropriate tools (optical power meter, light source, or copper testers) and validate polarity and connector cleanliness.

By handling the physical translation between device and medium, SFP modules enable modular, maintainable networks: they isolate physical-layer complexity inside a small, replaceable module while leaving the switching and routing hardware focused on forwarding logic and higher-level services.

4️⃣ Is SFP Used Only for Fiber in Networks?

No. One of the core roles of SFP in network design is media flexibility — the SFP form factor supports both fiber and copper transmission depending on the optical transceiver variant you install. Treat SFP as a modular physical-layer adapter rather than a medium-specific technology.

Below we explain the practical roles of fiber and copper SFPs, show common fiber SFP types, and outline specialized variants network teams should know when planning deployments.

Fiber SFP Modules and Their Role in Networks

Fiber SFP modules enable longer-distance, interference-resistant links and are widely used where reach, EMI immunity or greater bandwidth density are required. They differ by wavelength and optical design (LED/VCSEL for short reach vs DFB/DFB-like lasers for longer reach), which in turn determines the typical deployment role.

| Fiber SFP type |

Typical fiber |

Typical network role |

| SFP-SX |

Multimode fiber (MMF) — 850 nm |

Short-reach LAN connections (access/patching within buildings and racks) |

| SFP-LX |

Single-mode fiber (SMF) — 1310 nm |

Building-to-building and campus links (medium reach) |

| SFP-ZX |

Single-mode fiber (SMF) — 1550 nm (or other long-reach optics) |

Long-distance backbone or metro links (long-haul, may require amplification/repeaters) |

Practical notes

-

“SX/LX/ZX” are common marketing/technical labels. Always verify the datasheet for exact wavelength, transmitter type (VCSEL/DFB), and reach under specified fiber types (OM1/OM2/OM3/OM4 for MMF or specified SMF grades).

-

Reach claims are dependent on fiber quality, connector/splice loss, and environmental factors — use optical-budget calculations, not marketing reach numbers alone.

-

Fiber SFPs commonly use LC duplex connectors; polarity and patching conventions matter during installation.

Copper SFP Modules (RJ45 SFP) and Their Network Role

Copper SFP Modules present an RJ45 interface from an SFP cage and are effectively modular copper ports. Their role is to preserve port modularity while allowing use of existing twisted-pair cabling.

Key characteristics and roles

-

Provide standard Ethernet over twisted-pair (typically up to 100 meters) using Cat5e/Cat6/Cat6A depending on speed.

-

Useful in access-layer scenarios, short links between racks, or transitional deployments where fiber is not available or not cost-effective.

-

Keep inventory simple: a single switch SKU with SFP cages can support both fiber uplinks and copper access by swapping modules.

Operational considerations

-

Copper SFPs usually include an integrated PHY and magnetics inside the module.

-

They may expose less optical telemetry than fiber SFPs (DOM), so monitoring capability can be more limited.

-

Verify supported speeds (1G vs 2.5G/5G/10G variants) and power/thermal characteristics for the host.

Specialized SFP Variants

Beyond basic fiber vs copper, the SFP ecosystem includes variants that serve distinct network roles:

-

BiDi SFPs — single-fibre, bidirectional transceivers (paired wavelengths) used where fiber count is constrained.

-

CWDM/DWDM SFPs — wavelength-multiplexed optics for dense long-haul or metro links.

-

SFP+ / SFP28 compatibility — higher-speed variants use the same (or similar) mechanical cage but different electrical/thermal designs; don’t assume electrical compatibility without checking host support.

-

Industrial / extended-temp SFPs — for harsh environments (wide operating temperatures, vibration, etc.).

-

Passive/Active Copper (DAC) alternatives — direct attach copper or active optical cables may be used instead of discrete SFP modules for very short interconnects.

How to Choose: Role-driven Selection Checklist

-

Define the role — access, uplink, aggregation, or backbone? Choose fiber/copper and optics class accordingly.

-

Check media and reach — match wavelength and optics type to fiber grade and required distance; compute optical budget.

-

Verify host support — MSA form factor ensures fit, but check vendor compatibility lists and firmware requirements.

-

Confirm monitoring needs — if you need telemetry, prefer DOM-capable fiber SFPs or verify copper module monitoring.

-

Consider operational constraints — power, heat dissipation, and replacement logistics (spares & labeling).

SFP is a media-agnostic form factor that provides networks with flexibility: fiber SFPs for distance and EMI resilience; copper (RJ45) SFPs for short, economical links; and a range of specialized modules for constrained or high-density scenarios. The right choice is role-driven — identify the network function you need the port to perform, then select the SFP variant whose physical and operational characteristics fulfill that role. Always validate with datasheet values and host vendor guidance before procurement and deployment.

5️⃣ Why Do Networks Use SFP Instead of Fixed Ethernet Ports?

The strategic role of SFP in network infrastructure is to deliver scalability and adaptability: instead of replacing switches when requirements change, operators swap small, hot-pluggable modules to change media, reach, or speed. That tactical flexibility reduces downtime, lowers lifecycle cost, and simplifies operations in environments that evolve (campus upgrades, mixed-media data centers, or phased rollouts).

Key Benefits

-

Media flexibility: One chassis can support multimode fiber, single-mode fiber, or copper simply by changing the SFP.

-

Distance adaptability: Adjust link reach (short-reach MMF to long-reach SMF) without swapping devices.

-

Inventory efficiency: Keep a smaller set of spare modules rather than many device SKUs.

-

Hot-swap maintenance: Replace or upgrade transceivers with minimal disruption.

-

Futureproofing: Move from copper to fiber (or to higher speeds) gradually while preserving existing investment in chassis and line cards.

Tradeoffs and Caveats

-

Per-port cost vs chassis replacement: Individual SFPs add per-port expense (modules, optics), but they’re usually far cheaper than replacing chassis or line cards when media or reach needs change.

-

Thermal and power considerations: High-speed optics (SFP+, SFP28) and DWDM/CWDM optics may increase power/thermal load—verify host thermal budgets.

-

Vendor compatibility: MSA form factor ensures mechanical fit, but some vendors restrict third-party modules (firmware checks/vendor locking). Always verify compatibility.

-

Operational complexity: Modular ports increase SKUs to manage (module types, wavelengths, spare pools) and require disciplined labeling and lifecycle tracking.

Quick Comparison: SFP vs. Fixed Ethernet ports

| Dimension |

SFP (modular) |

Fixed Ethernet Port |

| Flexibility |

High — swap media/speed |

Low — fixed connector & media |

| Upgrade path |

Incremental, module swap |

Device/line-card replacement |

| Inventory model |

Modules + spares |

Device spares |

| Maintenance |

Hot-swappable |

May require planned downtime |

| Thermal/Power |

Variable by module |

Predictable per device spec |

Using SFP in network deployments is a pragmatic design decision: it treats the physical layer as a replaceable, upgradeable asset rather than a permanent constraint. When planned with compatibility, power/thermal, and inventory practices in mind, SFP-centric architectures deliver the agility modern networks require.

6️⃣ Common Types of SFP and Their Network Roles

SFP is a flexible form factor whose variants let network designers match physical-layer capabilities to specific roles. Below are the common SFP categories, what role each plays, and practical selection notes you can act on during design and procurement.

▶ At-a-glance Comparison

| SFP Type |

Typical role |

Key characteristics |

Typical reach |

| Fiber SFP (SX/LX/ZX, etc.) |

Uplinks, aggregation, backbone |

Optical transmitter/receiver, LC duplex, DOM often available |

meters → kilometers (depends on optics & fiber) |

| Copper SFP (RJ45 SFP) |

Access, short links, transitional ports |

RJ45 jack in SFP form, integrated PHY/magnetics |

≈100 m |

| BiDi SFP |

Fiber-constrained links, point-to-point |

Single-fiber bidirectional, paired wavelengths |

same as equivalent fiber optics but halves fiber count |

| CWDM/DWDM SFP |

Dense metro/long links, wavelength multiplexing |

ITU wavelength-tuned optics, passive/active muxing |

varies; used for wavelength-division multiplexing |

| SFP+ / SFP28 (higher-speed variants) |

10G / 25G links while preserving cage form factor |

Higher electrical/thermal demands; may fit same cage |

corresponding to optics class (SR/LR etc.) |

| Industrial / Extended-temp SFP |

Harsh environments (industrial/transport) |

Extended temp range, ruggedized packaging |

depends on optical spec, validated for env. stress |

| DAC / AOC alternatives |

Very short, cost- or latency-sensitive interconnects |

Direct Attach Copper / Active Optical Cables — fixed assemblies |

DAC: up to 7–10 m; AOC: longer, vendor-specific |

▶ Fiber SFP

Role: provide distance, EMI immunity, and stable uplinks for aggregation and backbone segments.

Selection tips:

-

Match wavelength and optics class to fiber grade (OM1–OM4 for MMF; specified SMF for SMF).

-

Prefer DOM-capable modules for managed links.

-

Calculate optical budget (Tx_min − Rx_sensitivity) and include ≥3 dB margin.

-

Verify transmitter type (VCSEL vs DFB) — DFB typically for longer reach.

▶ Copper SFP (RJ45)

Role: enable modular copper ports where legacy cabling or access-layer copper is needed.

Selection tips:

-

Confirm supported speeds (1G, multi-gig) and PoE compatibility if required (note: PoE via SFP is rare).

-

Check thermal load on the host — some copper SFPs dissipate more heat.

-

Expect limited telemetry vs fiber SFP Transceiver.

▶ BiDi SFP

Role: save fiber count by sending/receiving on different wavelengths over a single fiber.

Selection tips:

-

Pair BiDi modules with complementary wavelengths (e.g., 1270/1330 nm pair).

-

Ensure patching and polarity plans accommodate wavelength pairs.

-

Use when fiber infrastructure is constrained or splice/duct costs are high.

▶ CWDM / DWDM SFP

Role: increase capacity on existing fiber by carrying multiple wavelengths on one fiber (metro, provider aggregates).

Selection tips:

-

CWDM typically for less dense, cost-sensitive deployments; DWDM for high-density, amplified links.

-

Requires mux/demux and careful power budgeting (amplification alters optical budgets).

-

Check ITU channel and wavelength accuracy on datasheets.

▶ SFP+ / SFP28 and High-speed Variants

Role: enable higher line rates using the same mechanical footprint in many hosts.

Selection tips:

-

Mechanical fit ≠ electrical compatibility — confirm host supports the higher-speed PHY and signaling (e.g., 10G SFP+).

-

Higher rates increase power/thermal requirements; verify chassis cooling capacity.

▶ Industrial / Extended-temperature SFP

Role: provide reliable links in outdoor, factory, transportation, or extreme-temp environments.

Selection tips:

-

Look for stated operating ranges (e.g., −40 °C to +85 °C), shock/vibration specs, and conformal coatings if needed.

-

Validate reliability under real environmental stress (humidity, dust, thermal cycling).

▶ DAC / AOC Alternatives

Role: cost-effective, low-latency short interconnects between adjacent equipment (Top-of-Rack to switch).

Selection tips:

-

Use DAC/AOC for very short links to reduce per-port optics cost and simplify cabling.

-

For future flexibility, prefer SFP modules unless cost/latency strictly dictate fixed cable assemblies.

Picking the right SFP variant is about mapping role → physical capability → operational constraints. When that mapping is explicit and verified with datasheets and host acceptance testing, SFP-centric designs deliver maximum adaptability with controlled operational risk.

7️⃣ FAQs About the Role of SFP in Network

Q1: What is the role of SFP in network infrastructure?

The role of SFP in network infrastructure is to provide a modular, hot-pluggable interface that converts a device’s internal electrical signals into the appropriate physical transmission format. By using SFP modules, networks can support different media (fiber or copper), distances, and upgrade paths without replacing switches or routers, improving scalability and maintainability.

Q2: Is SFP only used in fiber networks?

No. SFP is not limited to fiber. While many SFP modules are optical, the same SFP form factor also supports copper (RJ45) SFP modules. The medium used by the port depends entirely on the SFP installed, not on the device itself.

Q3: How is SFP different from RJ45?

SFP is a pluggable transceiver module that defines how signals are transmitted and adapted to the physical medium.

RJ45 is a physical connector (8P8C) used only for twisted-pair copper cabling.

In short: RJ45 defines how a cable plugs in, while SFP defines how signals are converted and delivered.

Q4: Can one SFP port serve different network roles?

Yes. By swapping the SFP module, a single port can act as a short-reach copper access port, a fiber uplink, or a long-distance backbone link. This ability to change roles without redesigning hardware is a key reason SFP is widely used in enterprise and data-center networks.

Q5: Does using SFP affect network performance?

When properly selected and compatible with the host device, SFP Optical Modules do not limit performance. Link speed, reach, and reliability depend on the specific SFP type, its datasheet specifications, and correct deployment (optical budget, cabling quality, and host support).

8️⃣SFP in Network Conclusion

The role of SFP in network architecture goes far beyond simple connectivity. By separating switching logic from transmission media, SFP modules give networks the flexibility to adapt to changing distances, cabling types, and performance requirements without redesigning core hardware. From access-layer copper links to fiber-based aggregation and backbone connections, SFP enables scalable, maintainable, and cost-efficient Ethernet designs.

For modern enterprise and data-center environments, SFP has become a foundational building block: it simplifies upgrades, reduces downtime through hot-pluggable maintenance, and allows engineers to make physical-layer decisions at the module level rather than the device level. When selected and deployed correctly—based on datasheet specifications, compatibility validation, and proper optical budgeting—SFP modules deliver reliable performance across a wide range of network roles.

For engineers and network designers seeking reliable, standards-compliant SFP solutions — including fiber and copper transceivers with verified compatibility — explore detailed product options, datasheets, and technical resources at the LINK-PP Official Store, where components are built for real-world deployment and long-term reliability.